It’s common to hear people describe a suit’s silhouette in terms of its nationality. Suits are described as being American, British, or Continental. The first is either a sack or modified sack silhouette; the second said to be built up with military shoulders and have more waist suppression; and the third said to be a bit slimmer and feature “natural shoulders.”

This is roughly correct, though it stays truer for some countries than others. Jesse, for example, did a wonderful job of describing the traditional American style of suits a few months ago. His description really works for America because of how large J. Press looms in our sartorial history. For a country like Italy, however, it can be a bit more diverse. For example, a Neapolitan jacket can be very different from a Roman one, and some would say that Naples itself is also too heterogeneous to categorize. Thus, it can be useful to break down the silhouette of a suit into parts and not just think of them nationally. By doing so, you can better understand what you like or don’t like about a particular suit, and be better equipped to find one that best fits your personal sense of style.

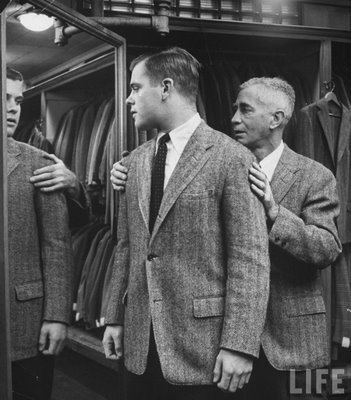

At the most basic level, a suit’s silhouette can be said to be either structured or soft. A structured suit will be made with a stiffer canvas and have a more built up, padded shoulder. A softer silhouette will, naturally, be made with a softer canvas and have a thinner layer of padding. A related issue, though not exactly the same, is the shoulder’s expression. A shoulder can be roped, natural, or bald. The first will have a prominent ridge at the shoulder seam that runs along the crown of the sleeve. The second will have a very light ridge, but run flat. The third will have a knocked down shoulder seam and very low profile. Jeffery Diduch did a great job of explaining the differences between shoulder expressions here. The takeaway is that while some expressions may be associated with specific styles of construction – for example, the bald shoulder with a softly constructed, unpadded shoulder line – they don’t necessarily have to go together. They’re two separate elements that work in concert with each other to make up what we see as the shoulder, which in turn gives us the impression of a structured or soft silhouette.

The minimally padded, softer silhouette is more popular these days, but that doesn’t necessarily mean you should wear it. One of the important lessons taught by Alan Flusser is that we should dress to our body types, not what happens to be fashionable. A friend of mine in San Francisco, for example, has a very round upper chest, as well as round, sloping shoulders with prominent blades. In a soft Neapolitan jacket, he looks like an gorilla, but in something more structured and with a nipped waist, he looks athletic and handsome. As always, it’s best to try both of these styles on and be objective about how you look in each.

The other important aspect to a suit is how lean or full it’s cut. In the most basic sense, this is about how close the suit sits to your body. Unfortunately, the trend of slimmer fitting clothes has led men to be single minded about this subject, but a better understanding is more nuanced. We can think of the suit in three parts – the chest, waist, and skirt (the skirt is simply the part of the jacket that hangs below the waist).

A lean chest will be shallow while a full chest will either be swelled or draped. A swelled chest will be fuller all around and look a bit more sculpted. A draped chest will have large, vertical folds of excess cloth that “drape” along the jacket’s edges, near the armholes. I made a post about drapes and swells at my other blog some time ago, and you can see illustrations of it there. The two often go together, but they don’t have to. You can have a swelled chest, for example, with no drape.

Similar to the chest, the waist can be nipped or left loose, and the skirt can hug the hips or be left a little full. These will create either a leaner or fuller silhouette, depending on how you combine these constructions.

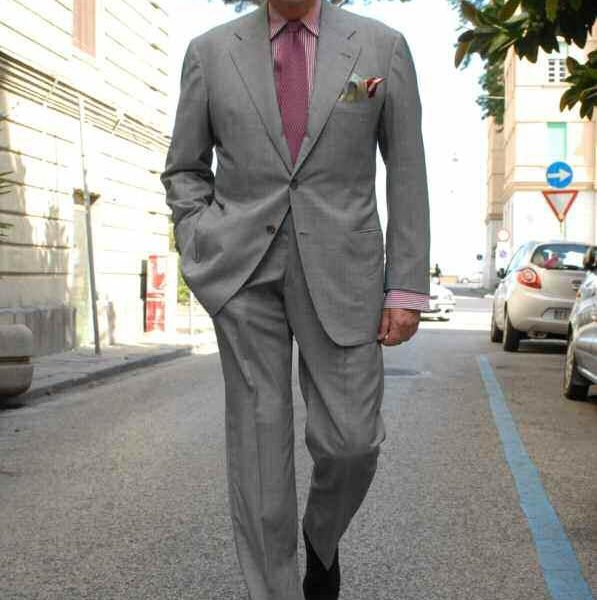

The “lean and clean” look is what men’s fashion magazines have been pushing for years, and probably what has been most popular with men for decades. This silhouette will sit closer to the wearer’s body in all three sections. A fuller silhouette is less popular, but I think unjustly so. I don’t just mean the dartless American sack suits here, either. Anderson & Sheppard, for example, makes a fuller chest that gently billows out a bit. I find the effect more masculine, heroic, and elegant. I once read Michael Alden compare someone’s “lean and clean” suit to an overly skinny runway model that needed more “meat on her bones.” Setting aside my slight discomfort with talking about people’s bodies in this way, his description spoke well to how I feel about these kinds of silhouettes in general. Of course, this is all a matter of personal taste and style, but I find fuller suits to have more depth and elegance, and be infinitely more interesting. Not that everyone should share my taste, of course, but I do think that most men should consider fuller suits more.

Moving on to the last dimension, a suit’s silhouette can either be elongating or widening. There are many aspects to this. An elongating suit will have a lower buttoning point. This will draw longer vertical lines along the suit’s lapel, which in turn will make the wearer look a bit taller. It may also have a higher gorge. A suit’s “gorge” is often conflated with the lapel’s notch, but it’s actually the seam that connects the jacket’s collar to the lapel. More or less the same, but still slightly different. Italians tend to make suits with a higher gorge than their British counterparts, and Neapolitan and Sicilian tailors make them higher still.

A widening silhouette will have wider lapels and perhaps extended shoulders. In today’s single-mindedness about suits, this may sound unappealing, but it’s worth reminding that many Neapolitan suits, which so many people are in love with nowadays, often have widening silhouettes.

In the end, all of these aspects can be combined in a number of ways to create an overall silhouette. One of the most elegantly dressed men I’ve ever met wore a softly constructed suit with a bald shoulder. His jacket had a fuller chest, nipped waist, and tight skirt. His trousers had a slightly higher rise and the legs were fuller than what more “fashionable” men wear today. They were still slim and flattering, however, and they created a nice line going from his jacket to his shoes. What he wore matched not only his body type, but also his personality and character. As a man, he was every bit as elegant as his clothes, and what he wore expressed him as a full human being, not as a clotheshorse.

As you look at pictures of well-dressed men, try dissecting each of these parts. You’ll develop a more refined understanding of suits and become more sensitive to how they can make an impression. Perhaps most importantly, you’ll be better equipped to purchase suits according to your body type and sense of style. Maybe you like lean, structured suits, or maybe you don’t, but you won’t know until you understand how to look for them.

Pictures taken from The Armoury, Permanent Style, The Sartorialist, Mister Crew, Rubinacci Club, and a few others I’ve unfortunately forgotten.