Swan Songs is a newly published book about a rapidly disappearing world of craft-based menswear. The author, Réginald-Jérôme de Mans, is a long-time friend and reader of our site. Since we’re at another crossroads in men’s clothing, where skyrocketing rents and increased competition have forced many more companies to close, we asked RJ to discuss how some of the themes in his book may apply to brands today. Why do some brands survive where others stumble and eventually fall? RJ shares his thoughts below.

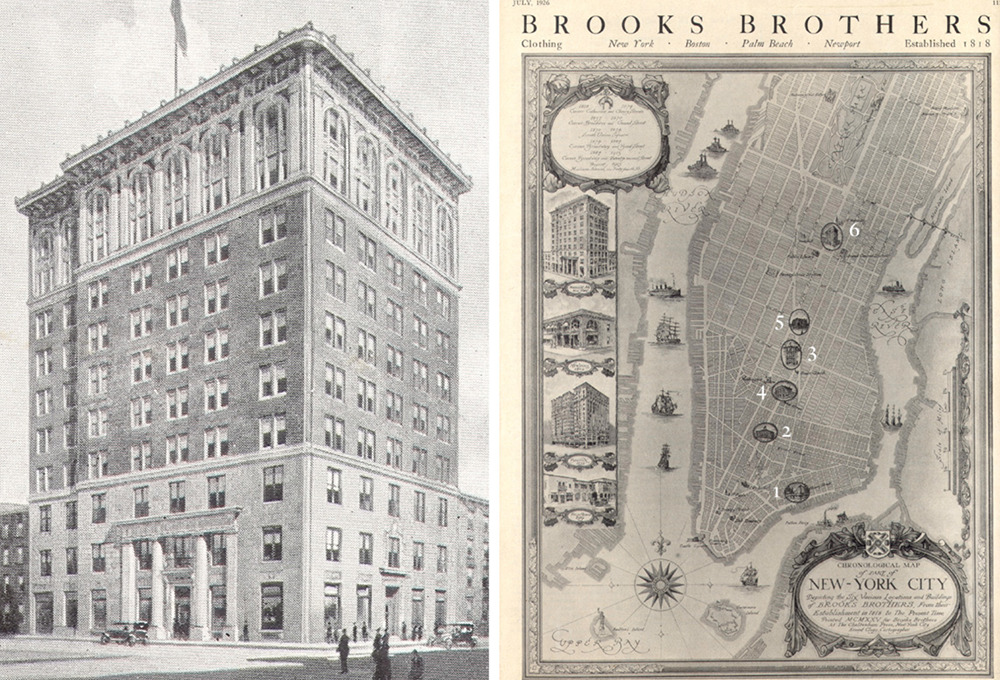

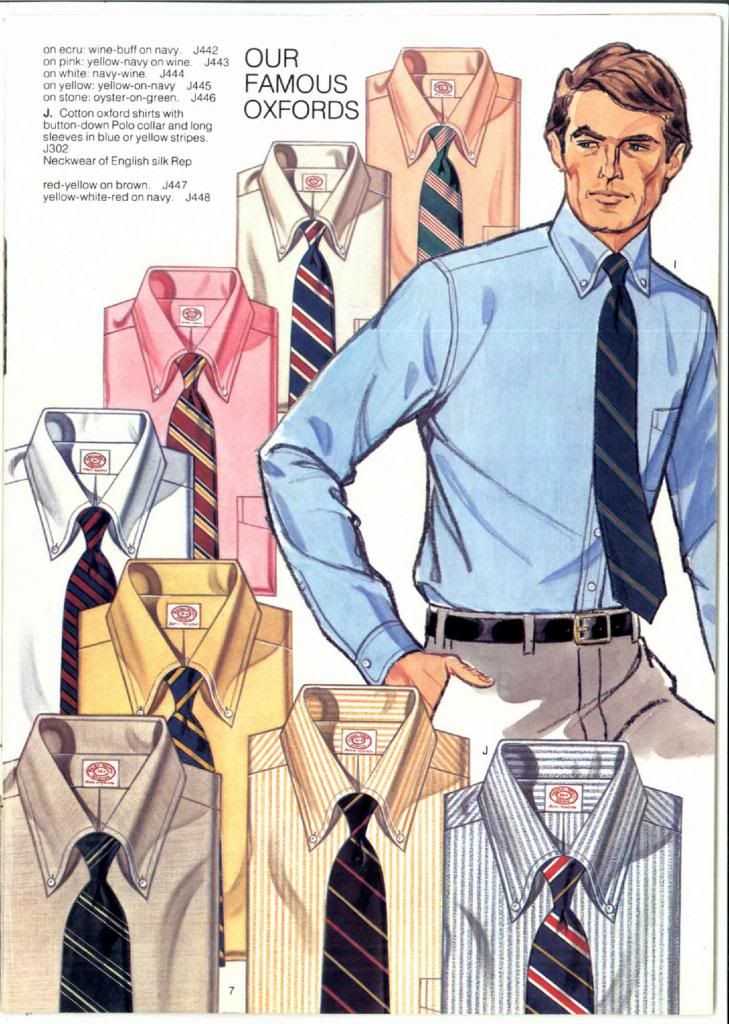

In the last two years, once-mighty players such as Brooks Brothers, J. Crew, and Neiman Marcus have filed for bankruptcy. So have Lord & Taylor, Stein Mart, and the company that operates #menswear bogeymen Men’s Wearhouse and Jos. A Bank. Beloved, cavernous fashion discounter Century 21 went out of business and closed its stores … and then announced it would reopen … somewhere. And even before the pandemic, changing tastes forced Ralph Lauren to restructure dramatically, terminating certain lines and closing some of its most splendid stores.

Newer brands dedicated to disruptive, direct-to-consumer models haven’t been spared. Last fall, Entireworld, makers of the fashion world’s favorite pandemic sweats, announced it was going out of business. It’s actually a rather more final step than the bankruptcies those other brands have entered. For the most part, Chapter 11 reorganizations allow large companies to restructure their existing debts and re-emerge leaner and more focused. That’s the spin, anyway, they give to their survival in a strange new form, as anyone who’s seen Brooks’ befuddling new mascot Henry the Sheep can see.

As the writer of a recent homage to departed and threatened French shops, I feel qualified to investigate how brands survive or stumble. Looking at who’s thrived and who’s died, is it possible to tease out the elements of the alchemy of survival? Let’s examine various traits one by one.

Agility

During the pandemic, white-collar workers have been driven mad with well-meaning sessions on mindfulness and resilience. Stores and brands can also benefit from a similar sort of flexibility, the agility to adjust quickly to changes in fashion tastes and shopping trends. For instance, the enormous Old England emporium in Paris, a century-old mahogany palace to British goods, could not adjust to the sudden accessibility of many British brands sold thanks to the Internet, the Channel Tunnel, and EU membership. It was no longer the near-exclusive source for its items and was burdened by what must have been enormous rents for a landmarked retail presence that took up nearly a city block. Its brand identity was bound up with that single, colossal shop, meaning that it could not wholesale its brand into other venues.

Similarly, Derek has perceptively written that Brooks Brothers was hamstrung by the leases, as it had to pay for a vast number of retail shops. Despite 80% of its sales coming from only 40 out of a total 250 shops, he learned that Brooks was often contractually bound to operate shops in a number of developments to keep its more lucrative shops in other areas.

In contrast, a brand with a relatively small physical footprint, such as Drakes, has continued to do well, including through wholesale and e-commerce – even if e-commerce does require its own particular infrastructure. Rents in high-profile parts of major cities keep rising, leading to the phenomenon of major brands using their flagship stores as loss-leaders: grandiose, unprofitable embassies for the brand that serve as marketing for the company’s wholesale, licenses, and accessories, which in turn subsidize those flagships. Michael Gross once suggested that Ralph Lauren’s major flagships were such loss leaders. Since the early 2010s, Ralph Lauren and Polo have retooled their lines and closed some of their large regional flagships, like the one near me where a boys’ choir in the gallery would surprise shoppers with carols at Christmastime. The Ralph mothership, the Rhinelander mansion in Manhattan, yet lives, of course, even as Brooks Brothers has closed its historic shop at 346 Madison.

Goodwill and Distinction

The closure of Brooks Brothers’ longtime 346 Madison address shattered what’s left of Brooks Brothers’ uniqueness in the canon of American fashion. Even if outlet shops and non-iron shirts buoyed the brand, 346 Madison’s array of classic Brooks Brothers products helped sustain the illusion of Brooks Brothers’ perennity, an unbroken heritage of classic quality. Some of those same items cropped up in odd corners of the Brooks e-commerce site, such as the lovely Edward Green shoes or inexplicable Kinloch Anderson kilt sock flashes, tassels that attach to the cabled socks you wear with a kilt, even as we stacked discount codes to plunder whatever sized socks the site had.

Both Ralph and Brooks Brothers enjoy considerable goodwill and positive recognition in the popular imagination for what they have done. Brooks Brothers surfed, then coasted, on its old reputation as the classic American outfitter … until Ralph Lauren repackaged all that was resonant and plangent about Brooks, the old Abercrombie and Fitch, and most of the classic college and sports outfitters of the American Northeast and West London. Both Brooks Brothers and Ralph Lauren played on iconography, Ralph rather more deftly. Brooks has never been able to broaden its identity beyond that reputation of classic establishment, at least not in any positive way, and it’s not clear it can ride Henry the Sheep back to relevance, even if appointing Michael Bastian as head designer is a nice counterstroke.

Diversification

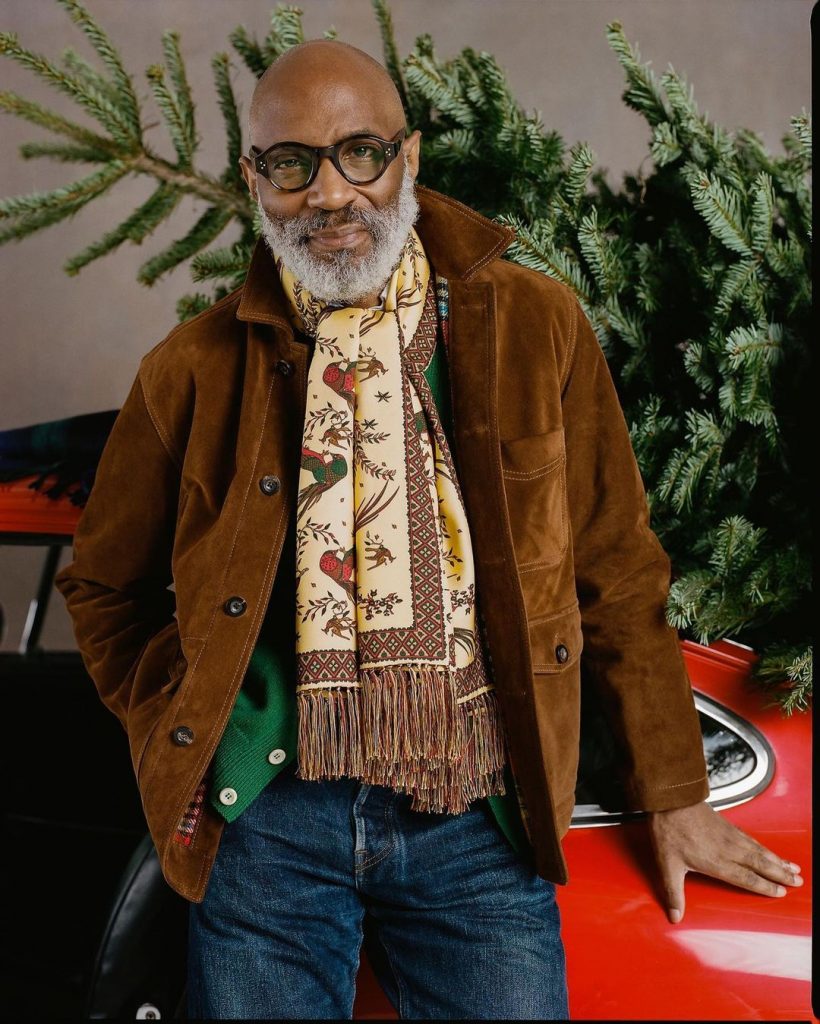

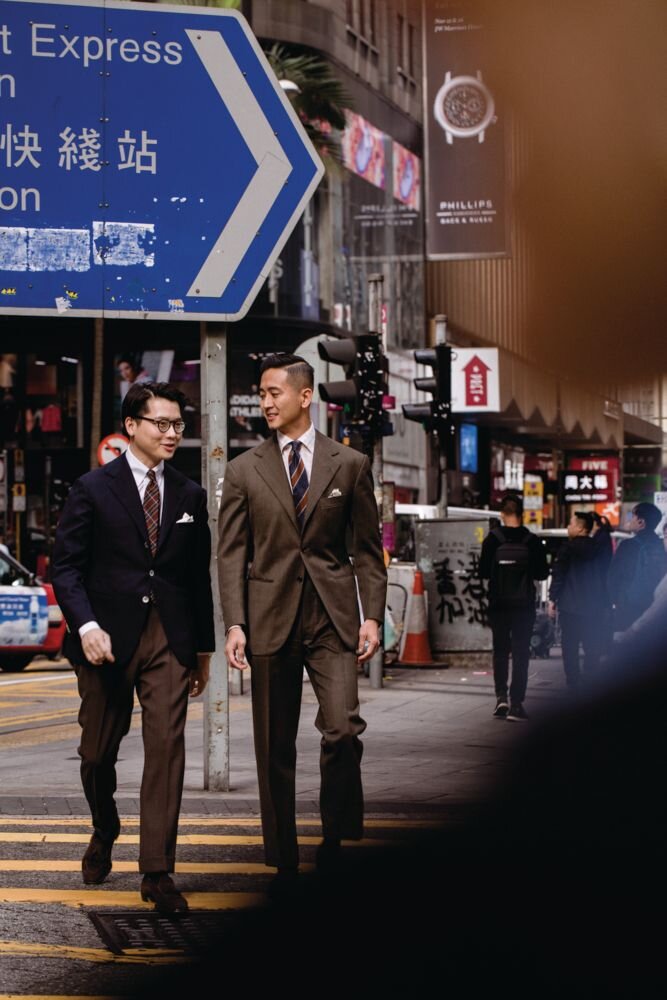

It’s important not to sink under the weight of your own heritage. Drakes began by selling scarves, then became England’s most prestigious tiemaker, which today may seem as secure a trade as top hat stiffener or sock garter tensioner. But in the last decade, it’s flourished by diversifying into other choice items of clothing that keep up with current style tastes, including suede chore jackets, classic but luxurious knitwear, coats in trendy Casentino cloth, and postmodern British takes on so-called collegiate and prep looks, which themselves had roots in American quotations of British style. Ties are no longer the affordably priced, easily wholesaled item that can keep an expensive brand afloat. Sulka, another brand I write about in my book, found it no longer could rely on that staple come the 1990s. Its management then tried to dress a faceless international corporate executive, expanding from Sulka’s traditional luxury dress shirts and ties into suits and casualwear, all in luxurious materials but extraordinarily bland and boxy designs and cuts. That attempt at diversification failed, becoming anonymization. In contrast, Drakes has constantly succeeded by producing products with either quirky utility (those chore jackets and cords) or fantasy (nobody needs a garment in Casentino cloth, whose texture looks like the super-pilled polyester blanket I had when I was six, or a scarf in the Dame à la Licorne prints Drakes… borrowed… from another French shop I wrote about).

Indulgent Parents

J. Crew, too, indulged customer fantasy for a decade with its lower Manhattan Liquor Store concept boutique, featuring Brigg umbrellas and other knickknacks. But that has also closed. Like Neiman Marcus, Sears, and Toys ‘R’ Us, J. Crew went through a leveraged buyout years before its bankruptcy. A leveraged buyout is private equity’s One Simple Trick: an investment firm takes out a lot of debt to finance its acquisition of a target company and then can transfer all of that debt to the company it just acquired, meaning that the company that was just bought has the burden of servicing the debt that was just used to buy it, while the investors who bought and own the company can declare themselves dividends out of the company’s earnings and transfer its assets to themselves. Neiman Marcus actually went through two leveraged buyouts in about a decade; the second set of buyers prompted lawsuits when they moved Neiman’s profitable MyTheresa e-commerce business to their ownership. In other words, many of the shops and brands that declared bankruptcy recently could have been profitable as going concerns were they not saddled with the debts used to buy themselves or stripped of money-earning assets. Neimans, J. Crew, and Brooks Brothers’ bankruptcies don’t mean they are closing: instead, they are successfully reducing many of their existing obligations. Some of those obligations are the debts to the creditors who financed their acquisition, but others are debts to suppliers, to the brands they retailed or those brands’ distributors, or the pension and other benefits that they had previously promised to their employees. So everyone, except these companies’ private equity owners, gets screwed.

In contrast, a J. Press or Paul Stuart can operate with relative security under ownership that for now seems focused on a long term, while Drakes has thrived at least in part because its current owners include Mark Cho of The Armoury, a tightly curated international boutique that thus far has operated with the care and attention of a labor of love. Its principals, whose devotion to taste and style comes out in their social media postings and public personae, show no sign of short-term profit-taking. But this is far from proof that there is any sure path for a brand’s survival on its own merits: meritocracy, on a corporate as well as human level, is one of capitalism’s red herrings, society’s figment barely concealing the supportive network that actually allows a brand, or a human, to thrive. It is indulgent corporate parents who care to invest in their holdings, or rapacious owners who strip and scour the bones of the formerly interesting, that make all the difference.