There’s a lot of talk these days about handmade clothes, but the truth is, almost everything you see today was made with a pair of hands pushing a piece of fabric through a sewing machine. There are some things that are truly handmade (e.g. our pocket squares), but the long seams you’ll find on shirts, coats, and pants are produced in ways that aren’t too different from how mom used to sew at home. That’s true whether the clothes were made in China or Italy.

In the future, however, it looks like that could change. Fast Company has a story about a new company called Sewbo, who’s invented the world’s first fully-automated sewing robot.

The reason why clothing production remains so labor intensive today is simple: fabric is flexible and flimsy, so you need a pair of human hands to skillfully guide it through a sewing machine. In the past, engineers have tried to solve this problem by coming up with machines that can emulate how a human sews, but that has proven difficult. So, Jonathan Zornow – the former Seattle software developer who founded Sewbo – approached the problem from the other end.

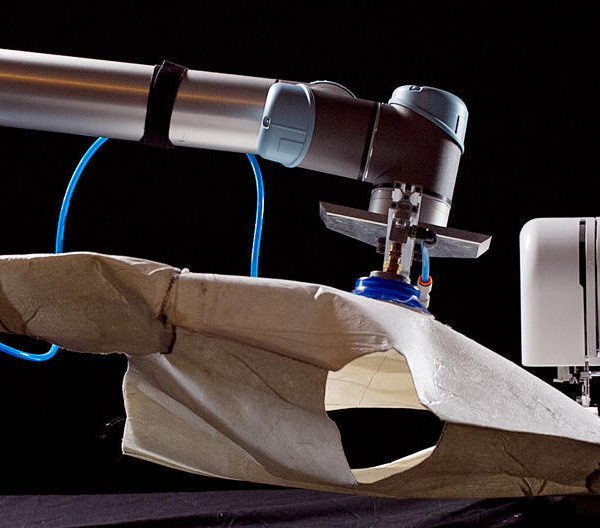

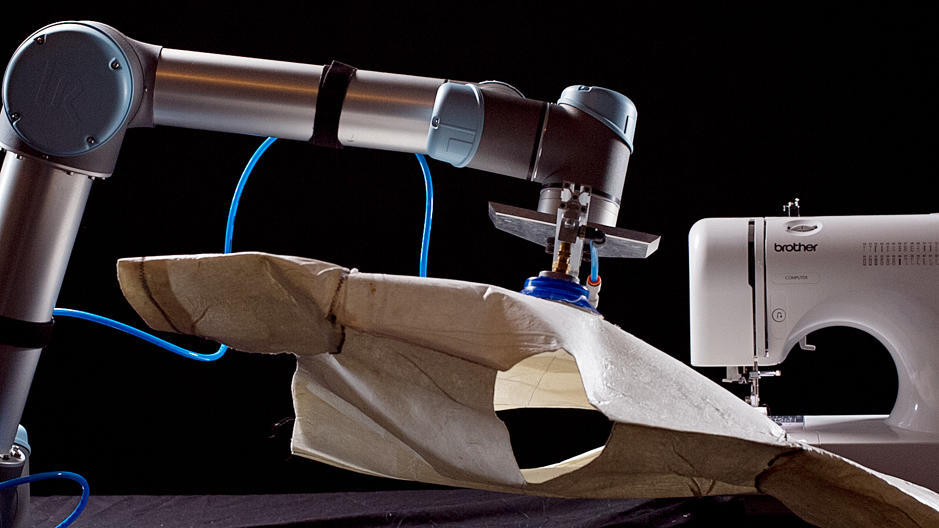

Zornow’s solution is ingeniously simple. Since machines are better at working with hard materials, he found a way to transform soft, flexible fabrics into hard composites by dipping them in liquid polymers. An except from the Fast Company article:

“They’re stiff as a board, but they can be molded: You can apply heat and reshape them, and when they cool down, they’ll hold their shape,” explains Zornow. The machine sews through the stiffened fabric to produce a perfectly finished product. (The process can be used with any sewing machine and most robotic arms, which generally cost about $35,000.) Afterwards, the polymers can be easily washed off with water, no detergent necessary.

There are, however, some limitations. Since the material needs to be completely wet, certain fabrics such as wools or leather are out of the question. But overall, even dry-clean-only goods like silks can go through the process. During a demo, it took roughly 30 minutes for the Sewbo process to complete a T-shirt, but Zornow believes it will take less time once it’s put on a manufacturing assembly line.

“I can say with some confidence that when it goes in the production environment, it will be at the same speed as a human sewer,” he holds. Unlike a human sewer, however, robots do not need breaks and are rarely subject to error.

You can see how Sewbo puts together a simple t-shirt in this promo video. The results are a bit rough, and the machine is extraordinarily expensive, but you can only imagine the technology getting better from here.

What does this mean for the future? It’s still unclear whether technologies such as this will replace human hands. After all, advanced machinery is expensive – much more than simple sewing machines and cheap international labor. Even if China’s wages are rising, there will always be emerging clothing production centers in low-cost countries.

However, if the long-run payoff ends up justifying the initial investment, you could see some reshoring of US jobs. That is, garment production moving from China and back into the US – but therein lies the catch. This kind of technology typically creates high-paying, knowledge-intensive employment, while at the same time, destroys low-paying, labor-intensive employment (e.g. more engineering jobs and fewer sewing jobs). Should garment production come back to the US, it’s unclear what the overall effect would be for sewing jobs given the amount of automation.

For a similar story, see this NYT article from 2015 about the reshoring of American textile mills. Two years ago, a Chinese company set up a textile production center in South Carolina, where a lot of cotton used to be produced. Given how much of the work today is automated, however, job creation has been minimal.

The work is highly automated, with the factory’s 32 production lines churning out about 85 tons of yarn a day. Even when Keer opens a second factory next year, it will hire just 500 workers, a fraction of the thousands of workers who toiled at cotton mills across the South for much of the 19th and 20th centuries — a big reason Keer is able to keep costs down.