One of the great things that has come out of menswear in the last twenty years is a better appreciation among men for the nuances of fit. You see the idea of a “perfect fit” being presented everywhere nowadays, especially with the emergence of more affordable custom tailoring. After the style excesses of the 1980s and ’90s, which were dominated by Armani, men found they often looked better if they just took in the waist of their garments a little more, sharpened up their trousers, and made sure shoulders seams actually sat on their shoulders.

It’s true that fit is king. If you’re clothes fit well, you can dress quite simply. But fit also isn’t the end all, be all of men’s style. In fact, it’s often just the starting point.

Genuine style is often more about silhouette than fit alone. The two aren’t totally distinct concepts — the lines are blurry and the two overlap. But generally speaking, fit in more meaningful terms is a very small area. It’s about whether a garment’s collar sits properly on your neck; whether things pull or bag where they shouldn’t. A silhouette, on the other hand, is about the shape of your clothes. It’s what’s left when you remove all the details and just look at the lines — and it’s the most important dimension for whether something looks good on you.

If you only pay attention to fit and think of it in overly broad terms, it’s possible that your clothes will technically fit well, but still look awful on you. The point of clothes, after all, is to flatter the shape of your body, not recreate it.

For the next couple of weeks, we’ll cover how to think of silhouettes — from traditional tailoring to casual ensembles. We start today with tailoring since the parameters are better defined and easier to discuss, although the principles here set the stage for next week’s discussion of casualwear.

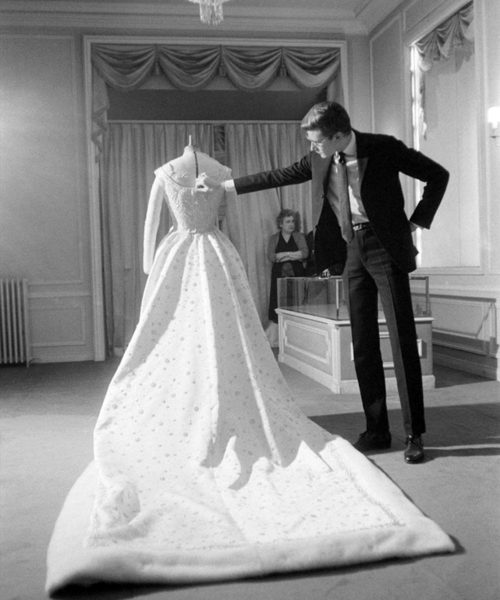

(photo via The Armoury)

Basic Terms You Should Know

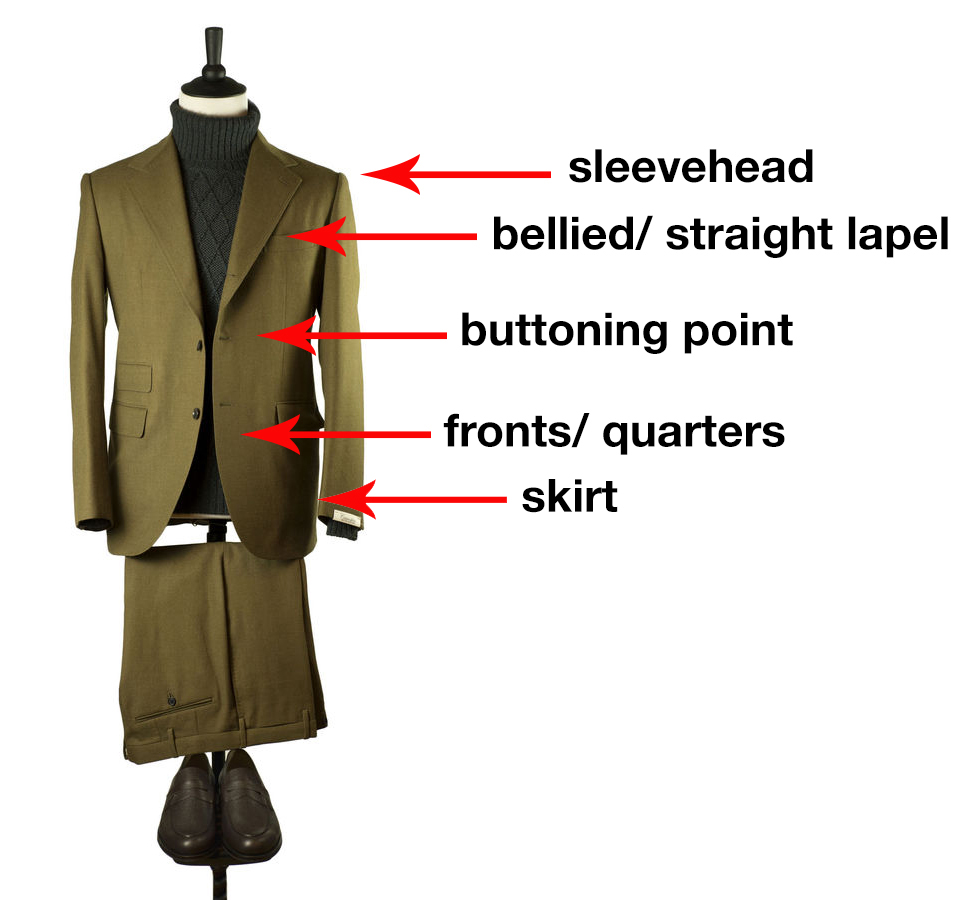

Let’s get some terminology down. If you’re thinking about how a suit jacket or sport coat looks, it helps to break the garment down into parts.

Sleevehead: The heart of a tailored jacket is in its shoulders, but how the shoulder line looks is about more than padding. A lot can change depending on how the sleevehead, which is the upper part of the sleeve, is inserted into the armhole. Jeffery Diduch, a professional tailor and pattern maker at Hart Schaffner Marx, explains it well in this post. A sleevehead can have a prominent ridge running along the crown (making it a roped shoulder); a light ridge, but still generally running flat (a natural shoulder); or be knocked down and have a low profile (a bald shoulder). Think of it as the punctuation mark at the end of a sentence.

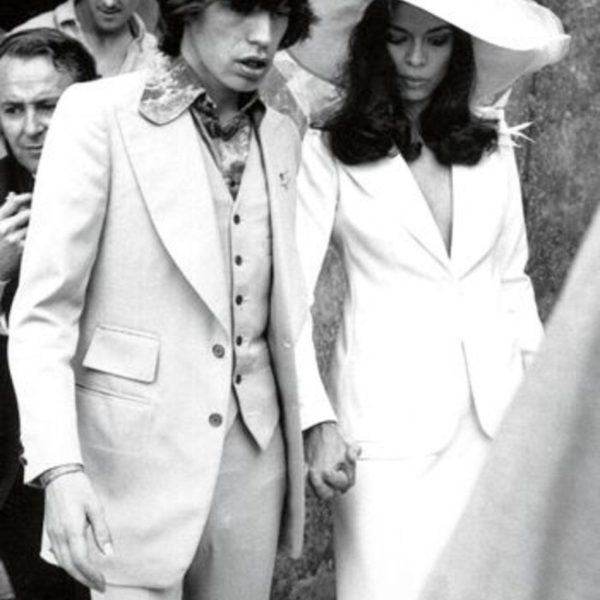

Bellied or Straight Lapel: If a lapel is curved along the edge, it’s known as a bellied lapel. If it doesn’t, it’s called straight. Bellied lapels were most famous on Tommy Nutter and Edward Sexton’s creations in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, back when they dressed the Beatles, Mick and Bianca Jagger, Elton John, and Diana Ross. Their suits were distinctive – broad shouldered with a nipped waist, flared skirt, and these wide, curvy lapels that looked like the outer edges of a family crest. Bellies aren’t always so extreme, of course. Many, if not most, traditional tailoring houses put some kind of curve on their lapels, you just have to look harder to spot them. A curve will give a jacket a more old-school appearance, whereas straight lapels can feel very modern.

Buttoning Point: This is the jacket’s fulcrum. On a two-button jacket, it’s the top button. On a three-button jacket, it’s the middle. A classically cut jacket will typically have the buttoning point placed at the waist, the narrowest part of the garment, although as hemlines have crept up in the last fifteen years, so have buttoning points.

Fronts / Quarters: The area of your jacket that opens up below the buttoning point. Open quarters (or fronts) sweep back towards the hips, giving the jacket some visual dynamism. Closed quarters, on the other hand, are a bit more conservative.

Skirt: Whereas quarters refer to how a jacket opens below the buttoning point, the skirt is the general area. Back in the day, equestrian coats used to be made with what’s known as a flared skirt, so that the wearer’s jacket would splay more neatly across a saddle. Today, it’s done for stylistic effect. A flared skirt will generally give you an X-shaped silhouette. A skirt that hugs your hips, on the other hand, will give you a Y-shaped figure.

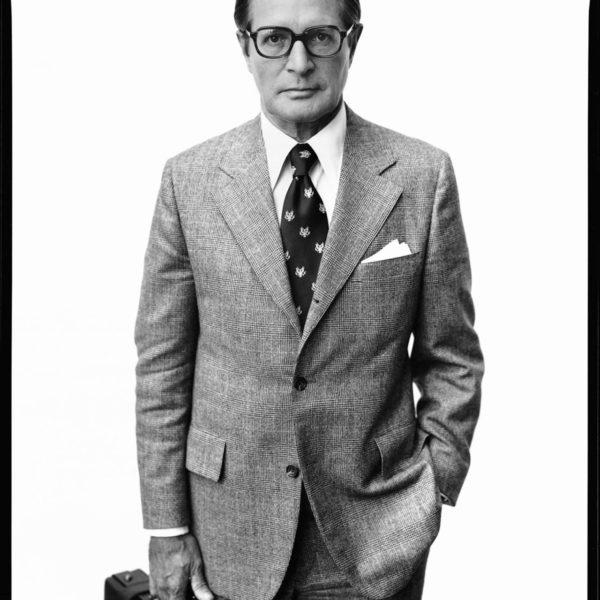

(photo via No Man Walks Alone)

Lean and Clean vs. Drape and Shape

In the world of suits and sport coats, the biggest divide is between those who prefer a lean and clean coat, and those who like things draped and shaped. Or, put more simply, those who like a slim fit versus those who like things fuller.

Drape is a funny word because it’s often used to refer to how a garment hangs — whether a jacket “drapes well,” as they say. But in more technical terms, tailors use it to refer a very specific cut. In the early 20th century, a Dutch-English tailor named Frederick Scholte noticed what happens when you belted up a Guardsman’s coat — the chest became a little fuller, the waist nipped, and the overall silhouette looked more masculine and athletic.

Scholte incorporated a similar look into his suits and sport coats. By strategically cutting the panels in a certain way, and filling the interior with a chest piece that’s been cut on a bias, he was able to create a chest that sits slightly off the body. The drape cut, as it’s known, refers to how the excess fabric “drapes” near armhole. And like the Guardsman coat, it gives the wearer the illusion of a more athletic figure.

One of Scholte’s clients was Edward VIII, the Duke of Windsor, who was one of the 20th century’s most influential style figures. The Duke wore the drape cut, and then it later spread through Hollywood. And from there, it was picked up by jazz musicians and morphed into the zoot suit. Today, the cut is mostly carried on through Anderson & Sheppard (the company’s co-founder, Per Anderson, trained under Schlote). Daniel Day-Lewis wore Anderson & Sheppard for his role in the film Phantom Thread. Steed, one of my tailors, is another company that specializes in this look.

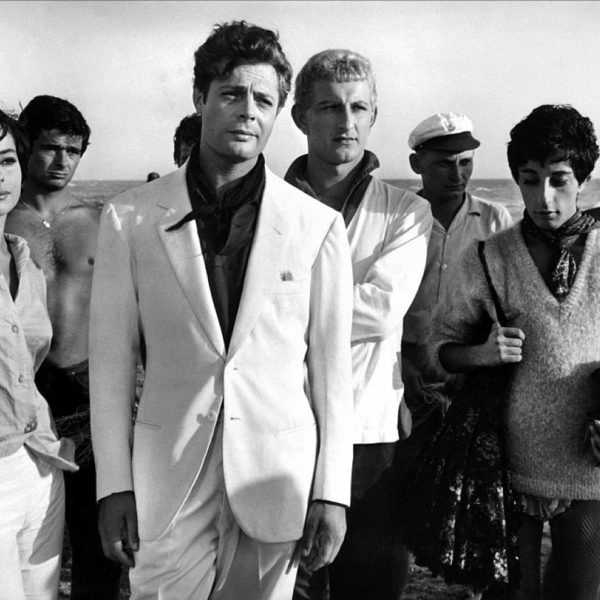

You can see how the drape cut looks on Maurizio Marinella in the first photo above (he’s the man holding all the ties) and the first three photos in the gallery. Notice how excess fabric “drapes” along the edges of the chest, near the armhole, giving the cut a fuller and more sculpted appearance.

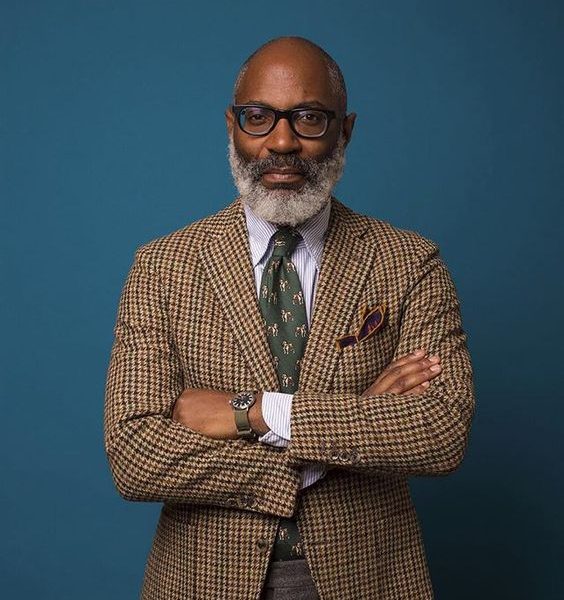

Opposite to this is what’s known as a “lean and clean” cut, which is another term for a slim fitting coat. The chest sits closer to the body; the overall fit is a little tighter. There are hundreds of variations on this style — Hedi Slimane’s work at Dior and Saint Laurent are the most extreme, but there are also plenty of traditional tailors who make more moderate, clean looking suits. And you often see the style in contemporary lines, from J. Crew to Patrick Johnson to Drake’s (which are pictured above).

Note, either style can be made with soft tailoring, but there’s a limit to how much structure you can remove from a drape cut. Lean and clean coats, on other hand, can be totally deconstructed, which means there’s little to no padding inside. These sorts of coats can have a very casual and easygoing feel, but as you remove more and more structure, you have to cut the coat closer to the body. And, in doing so, the suit or sport coat will reveal more than it hides. Be honest with how these sorts of garments look on you. Unless you have a naturally slim or lean-athletic figure, they can make you look like a dressed-up pear.

(photos via E. Marinella, J. Crew, Voxsartoria, BRIO, P. Johnson Tailors, Drake’s, and Tutto Fatto a Mano)

Elongating vs. Widening

More than just slim or full fitting, the lines around your jacket can give you a longer or wider appearance.

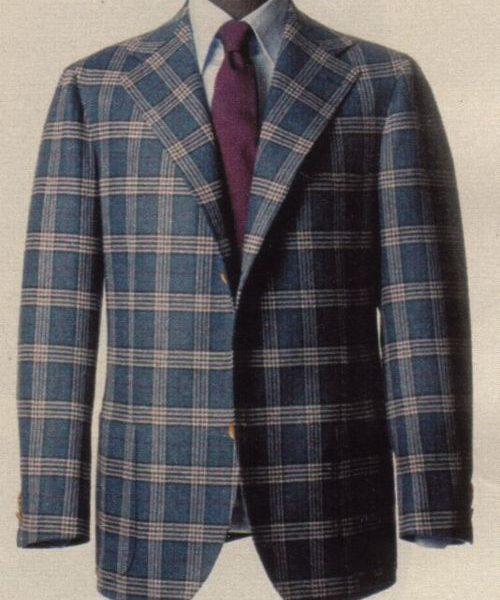

Why would anyone want to look wide? Well, in certain cases, the cut can look a bit more casual, relaxed, and frankly awesome. Liverano & Liverano, a bespoke tailoring house based in Florence, Italy, is known for their softer, rounder silhouettes. The jackets are cut a bit shorter, the lapels wider, and the shoulders have a softer, more natural appearance. The overall silhouette is rounder than the columnar coats from Gieves & Hawkes.

Conversely, a suit can also be elongating. The jacket might be cut in a more traditional length (which, in some cases, can actually be slimming). Dropping the buttoning point and moving the notch upwards can also elongate the lapel’s line. In the gallery above, you can see the difference this makes in the last photo, where Luca Rubinacci’s jacket has a longer, more elongating silhouette than his father’s suit.

The curve, or lack thereof, on a jacket’s lapels can also affect the shape of the coat. Notice how on Liverano’s suits, the lapels almost curve inward along the edges, forming two half moon semi-circles once you draw a line going from the top of the shoulders down to the hem. They have a ) ( shape when viewed from the front, moving your eyes towards the edges. Luca’s razor sharp, straight-sided V-shaped lapels and relatively closed quarters, on the other hand, are more vertically orientated.

(photos via The Armoury, The Sartorialist, Die, Workwear, Ethan Newton, Voxsartoria, and Rubinacci)

Overall Shape

When looking at a suit or sport coat, think of how all these elements play into its general silhouette. Ask yourself:

- How Do the Shoulders Look? Are they soft or padded? How do the sleeveheads affect the shoulders’ expression? Do they look narrow relative to the rest of the ensemble? Should they be extended? Sometimes extending the shoulders can help you achieve a better V-shaped figure, making your waist look smaller by comparison.

- How are the Lapels Cut? Are the lapels narrow or wide? Are they cut straight or do they have a curve? How do they play with the rest of the coat, including the shoulders and quarters?

- Quarters and Skirt: Are the quarters open or closed? Does the skirt kick out or hug the hips? Like extended shoulders, sometimes a flared skirt can help give a coat some added shape.

- Chest Shape and Lines: Is the coat cut lean and clean, or draped and shaped? Would the chest look better with some fullness and shaping? How do the lines on the coat interact with each other? Do they elongate or widen?

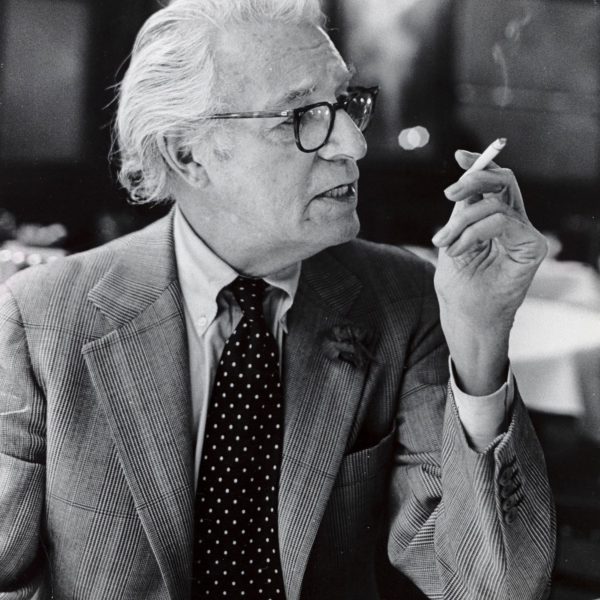

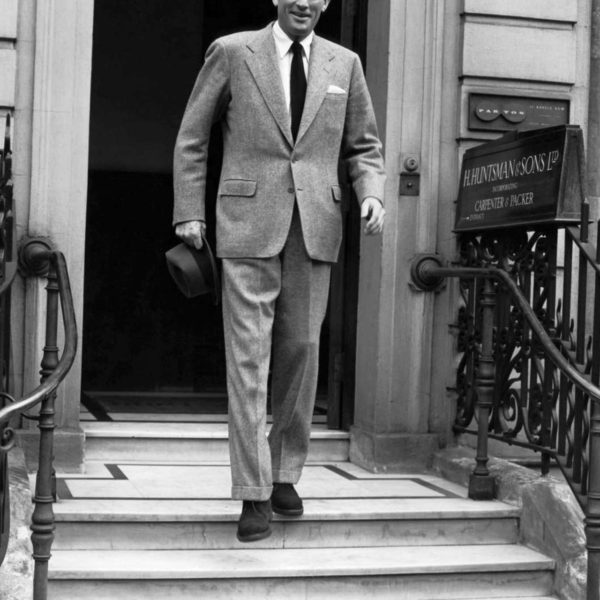

- Rounded or Angular: Does the coat look rounded or angular? In the photos above, you can see how B & Tailor’s tan gabardine suit looks a bit rounder. The coat’s silhouette is defined by its soft, extended shoulders, wider lapels, and curvy, open quarters. The men at Huntsman, on the other hand, are wearing straight lapels, angular quarters, padded shoulders, and slightly flared out skirts. Which, by comparison, give them an angular X-shaped figure.

Once you get the hang of looking at a coat’s shape, you’ll understand what distinguishes one plain navy worsted suit from another. Perhaps most importantly, you’ll be better equipped to purchase suits according to your body type and sense of style. Suits and sport coats come in an alphabet of shapes: As, Xs, Ys, and columnar Is. Think about what shape you want to achieve.

Come back next week for a discussion of how silhouettes can be expressed in casualwear.

(photos via B & Tailor, Huntsman The Sartorialist, Blue Loafers, Andreas Weinas, The Rake, Mark Cho, Die, Workwear, Voxsartoria)