If you’re traveling and want to do a bit of menswear shopping, you have to trawl the internet for tips. The retail landscape in almost every city nowadays looks the same — shopping districts are covered with the same J. Crews, Gaps, and Nordstroms, just as almost every street corner in America has a Starbucks or McDonalds. To find something special, you have to know where to look.

Things weren’t always like this. Up until about the 1970s, each city had its own unique cluster of retailers, serving just that district and no one beyond its borders. And you could walk down Main Street and find things you couldn’t get anywhere else. There was FR Tripler in New York City; Harvey in Providence; Britches in Georgetown; Lewis & Thomas Saltz in Washington; and Jacob Reed’s Sons in Philadelphia, just to name a few. If these names sound unfamiliar, it’s because they have long closed and been since forgotten. Of the small and independent menswear retailers that exist, they’re mostly in casualwear.

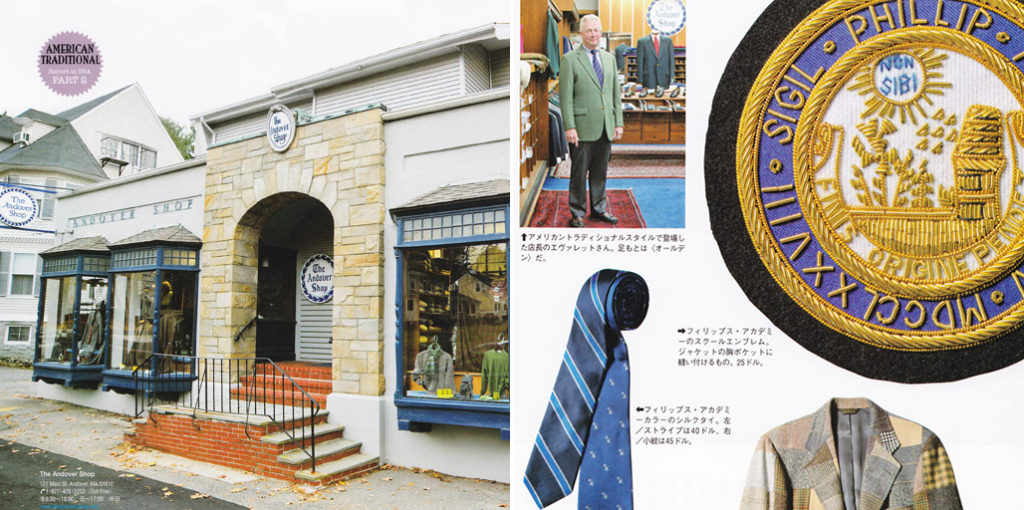

Small, independent shops — specifically those specializing in traditional suits, sport coats, and “furnishings” (e.g. ties, pocket squares, and dress belts) — are a dying breed, but they’re still around. They just number in the dozens. And news of their troubles sends big waves throughout the traditional menswear community, as the closing of any one can make a big difference. In just this past year, it was announced that The Andover Shop and The Hound are looking for new owners, as their current management is looking to retire. And J. Press recently got booted out of their Harvard Square location just last month after 86 years of doing business there.

“J. Press had been in negotiations with the building’s landlord for terms to maintain its current location on Mount Auburn Street,” the company’s president said in a statement. “However, the two parties were unable to come to an agreement. J. Press takes its history at this location very seriously and tried to work for a way to keep it, but given the increasing rents in the area over the past several years, it did not work.” At the moment, J. Press is still looking for a new location in the Cambridge area.

J. Press’ now closed Cambridge store

The challenges these retailers face won’t shock anyone. As dress codes have gotten increasingly casual, these shops have seen a shift from suits to sport coats, and then from sport coats to something even more dressed down. “When I moved into this location 25 years ago, I carried a couple thousand suits and had five tailors working for me,” says Walter Schorno, founder of The Hound. “Now if I carry three hundred suits, that would be a lot. I used to carry 5,000 ties and now I have a fraction of that number.”

Almost every retailer we spoke to also tells us they do brisk business in sweaters, as working professionals have replaced tailored jackets with knitwear. This is important. People’s closets are only so big, and they only need so many clothes. If they’re building a work wardrobe, and can replace suits with sport coats, and then sport coats with knitwear, that presents challenges to small, traditional clothiers. A two-week wardrobe full of sweaters, chinos, and sneakers isn’t nearly as profitable as one with sport coats and tailored trousers. Or better yet, suits and their accouterments.

Add to this all the same challenges other brick-and-mortars face: consumers becoming shrewder about comparison shopping online; brands undercutting their own retailers by selling directly to customers; and perhaps most of all, exploding real estate costs. The moment for prep in the fashion spotlight has also mostly passed. Whereas there used to be a steady stream of younger consumers going to Brooks Brothers — and some of the more discerning few seeking out smaller, more “authentic” stores — many of those people have now moved on to streetwear and designer clothing.

That said, it’s been interesting to see how some of these smaller shops have been able to survive, sometimes even thrive, in this environment. One of the stronger businesses is O’Connell’s in Buffalo, New York. Like many trad shops, here you can find close-set racks of heavy tweed sport coats, traditional English outerwear, rep striped ties, oxford button-downs, and brightly colored Sheltands (the last being my favorite — seriously, the sweaters here are tremendous).

O’Connell’s massive sweater section

O’Connell’s success is almost fortuitous. They’ve owned their own building since 1960, which has protected them from the boom in real estate costs. The building is a 10,000 square foot property with three stories and two separate basements — just enough space to house their expansive (perhaps even overwhelming) inventory. O’Connell’s has one of the biggest trad selections anywhere, with tattersall shirts of every color combination and trousers in every material.

They also have a sizable web presence. “Twenty years ago, it was O’Connell’s dot net,” says Ethan Huber, who co-owns the shop with his family. “It was just a splash page with a few photos, but people could use the photos and order something via phone. Then, about ten years ago, we put up a functional checkout system that allows people to shop online. And since then, business has been growing steadily every year. Frankly, the real challenge here is trying to keep up.”

Over half of O’Connell’s business now comes from online sales. They sell to trad enthusiasts around the world, from England to Japan to Australia (Australia being the biggest international market, oddly). “There are a lot more people out there than roaming down Main Street in Buffalo,” says Ethan. “We’ll never sell more in-store than we do online, at this point.” He suspects people come to him because he carries things you can’t easily find at shops such as Ralph Lauren — original oxford button-downs like Brooks Brothers used to make before the late 1990s; harness weight suits; and saddle-shoulder Shetlands in nearly every imaginable color (have I mentioned those Shetlands are really good?).

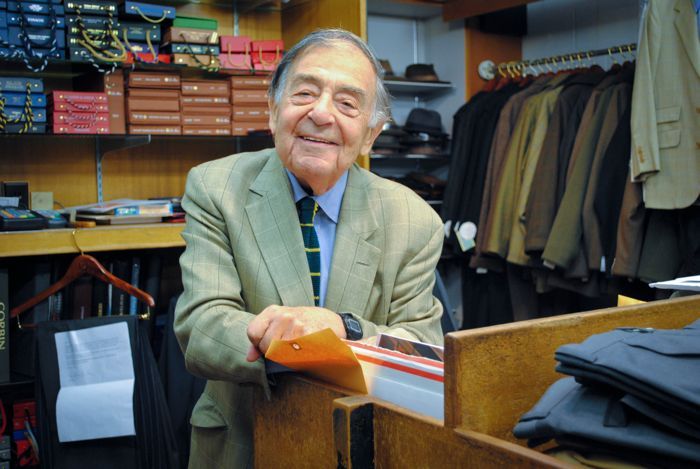

Charlie Davidson and The Andover Shop

Other retailers haven’t been so keen on e-commerce. The Andover Shop’s Charlie Davidson, in his usual, charmingly gruff way, once told Christian Chensvold at Ivy Style that he “can’t believe anyone with taste would buy anything over the Internet” (Andover actually does have a webstore, although it’s not as built out as O’Connell’s). When I pressed Schorno at The Hound on why he hasn’t ventured into e-commerce, he said, plainly: “Probably because I’m 81 years old. It costs money to do an internet business, and you have to have people that understand that side of things.”

This has forced many of these companies to focus on in-person service and, often, things that don’t allow for easy comparison-shopping. A chunk of Andover Shop’s business, for example, is in made-to-measure jackets, which is done in-person by experienced sales associates with years in the custom tailoring trade (but at prices that aren’t much more than Brooks Brothers ready-to-wear).

“Our business is focused on very individualized service, so that if someone comes in, we can ferret out exactly what they need,” Andover Shop manager, Larry Mahoney, tells me. “If someone comes in for a sport coat, we can try on a variety of jackets and find the best fit. Maybe we go off-the-rack; maybe we do custom. If we do custom, we have more fabric options than what most stores offer, but also a sales staff that can help you narrow in on the best choices for your needs.” Many of these smaller, more traditional retailers rely on their unique sense of taste and specialized service to distinguish themselves from the Suitsupply companies of the world, where you can get a suit for $400 — less than what an American-made suit costs wholesale.

Likewise, Cable Car Clothiers’ main business is still in tailored clothing, but they’ve seen the hat side of their shop grow to almost 40% of their sales. “Hats are a very hands-on experience,” says Jonathan Levin, the shop’s owner. “You can’t shop for it online as easily. You need someone to tell you how to size something, how to choose a style, and whether something works for your face. We do that for our customers in-person.”

Cable Car Clothiers in San Francisco

The other challenge has been bringing in new customers. At Cable Car Clothiers, you can find a full barbershop service, which Levin notes sometimes introduces new customers to their clothing section. And at Andover, they’ve worked to make their clothes more attractive to younger customers (about 25% of their business is still to Harvard undergrads who need something to wear to club events). “As older customers retire, you have to evolve to meet the needs of a new and ever changing market, says Mahoney. “Our jackets are trimmer nowadays. They’re not particularly short or anything, but they’ve been updated a little. You’ve bought a made-to-measure jacket as an investment that you can wear for the next twenty years, but it doesn’t have to be a sack coat. It can be more form fitting. We don’t carry blue jeans, but we do have five-pocket trousers. And many of our jackets are side vented.”

It’s easy to get down on the prospects for these shops, but there’s a happy side to this story. The real culling for small and independent trad clothiers happened in the 1970s and ’80s — those that survived are now mostly doing well. Even if they face similar challenges (e.g. keeping up with rents, having a line of succession, and finding ways to adapt to changing dress norms), everyone still needs a suit. There are still attorneys and other white-collar professionals, as well as people who simply need things for weddings and funerals.

“When I started The Hound, there was a traditional clothier in every city. Now in the Bay Area, it’s just us and a few others, so we’re basically at the end of the funnel. We get all the customers who want a certain traditional look,” says Schorno. “In the future, there will always be a big space for stores such as mine; very little space for companies such as Nordstrom. As wages and rent goes up, good clothing is going to cost a lot more money. And people are going to want real service — sales associates who know what they’re selling. That’s going to be the market for specialized boutiques.”

The heads of the other shops agree. “There are a lot of guys out there who don’t even own the basics. A navy blazer, a white oxford-cloth button-down shirt, and some good shoes,” says Levin. As Mahoney sees it, “the market is really untapped.”

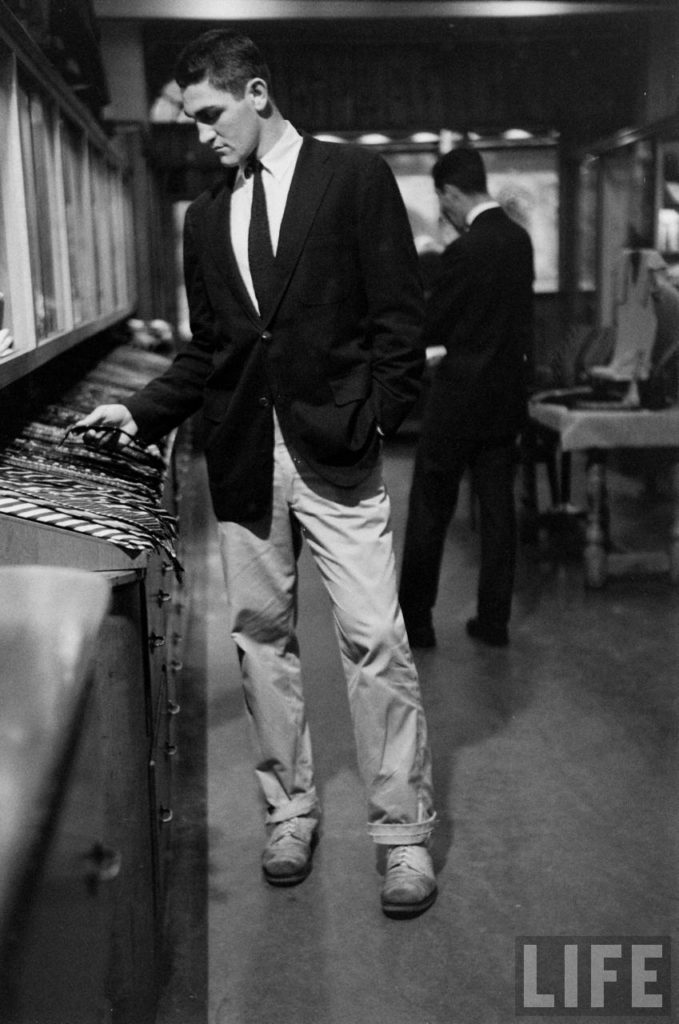

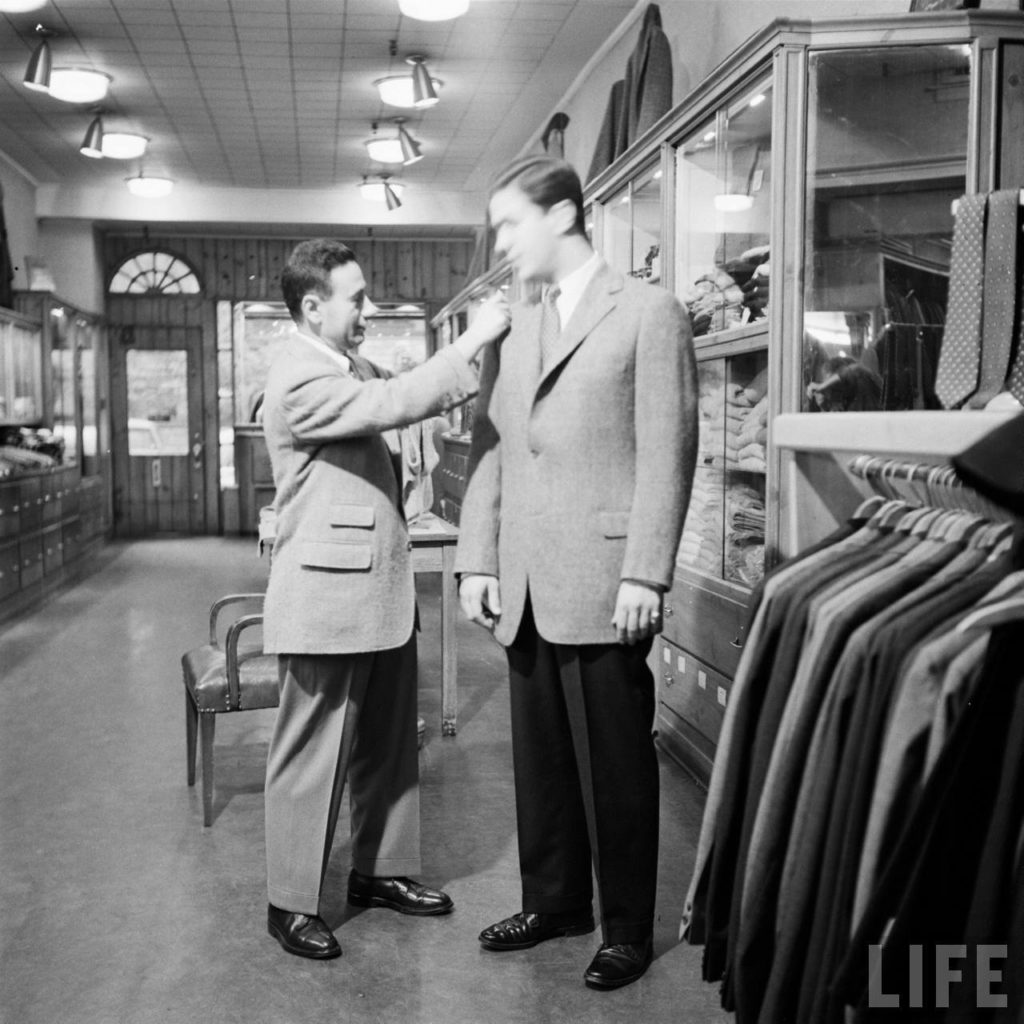

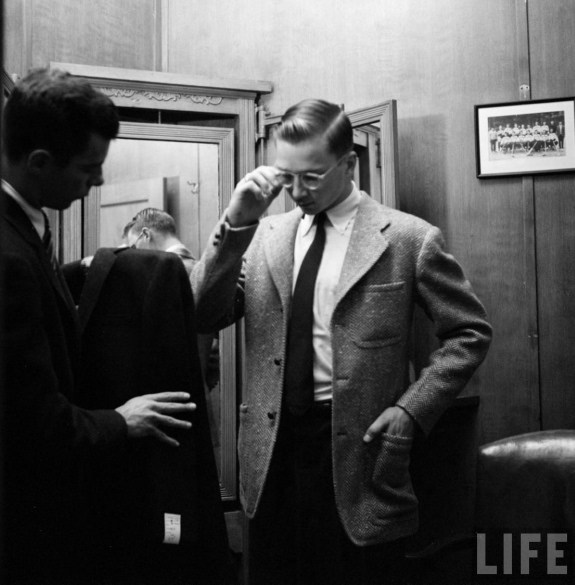

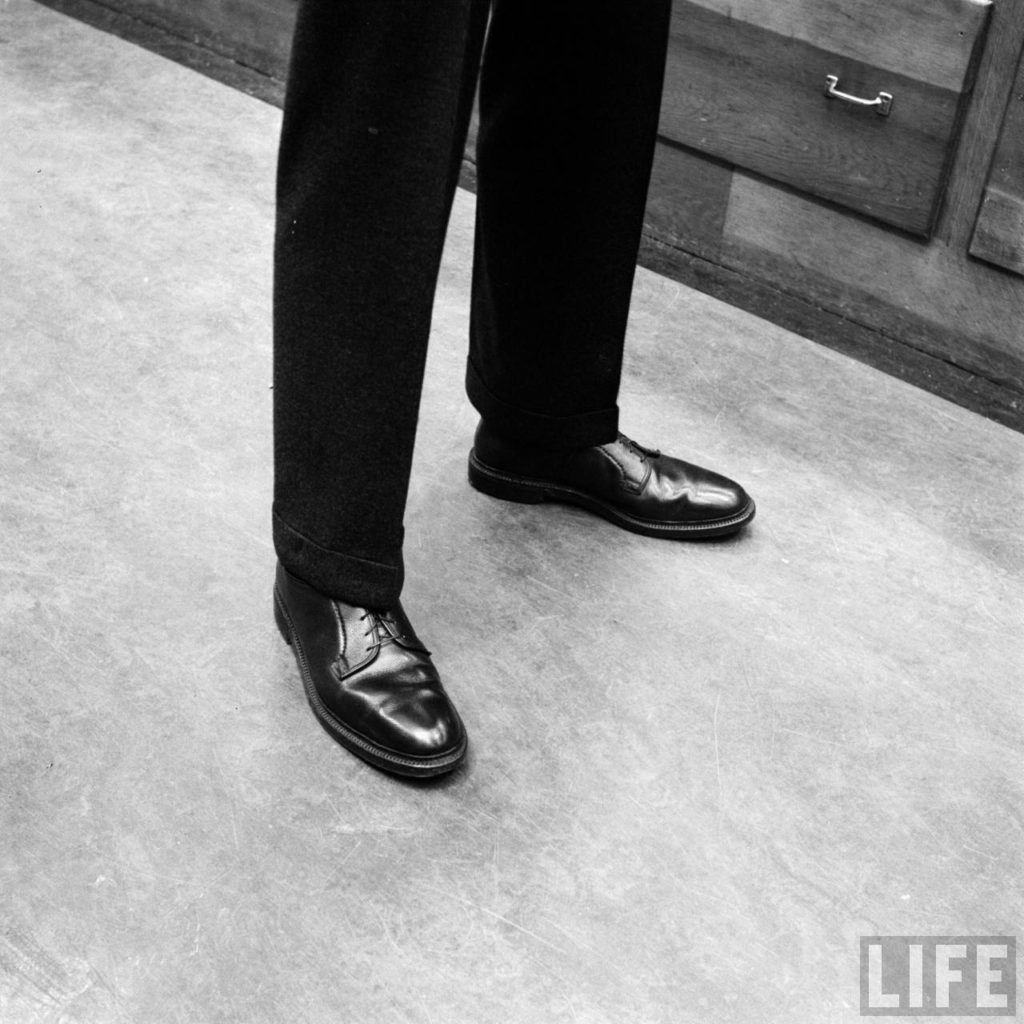

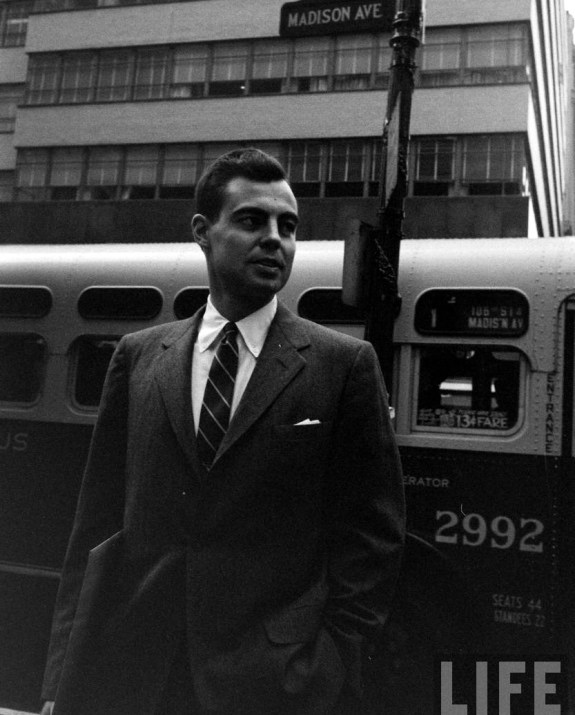

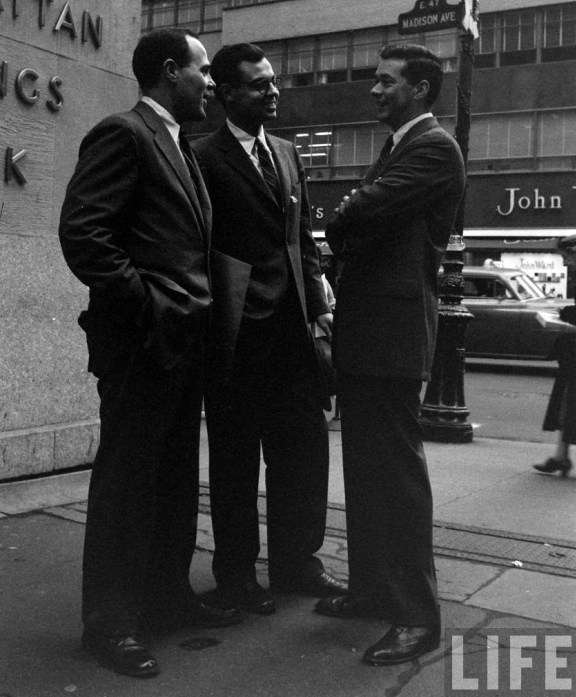

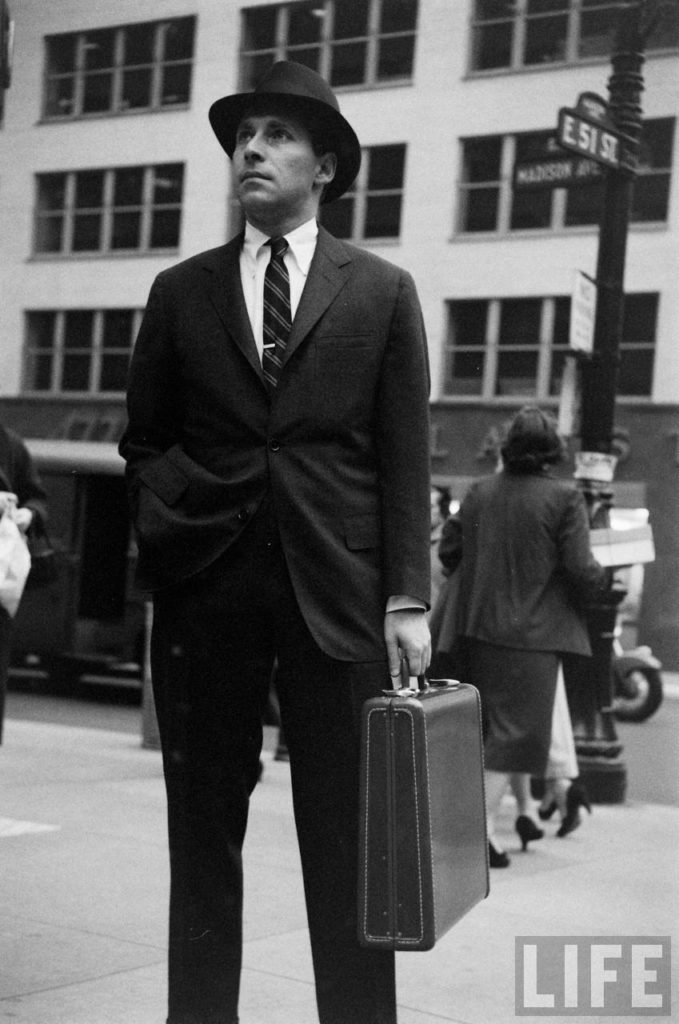

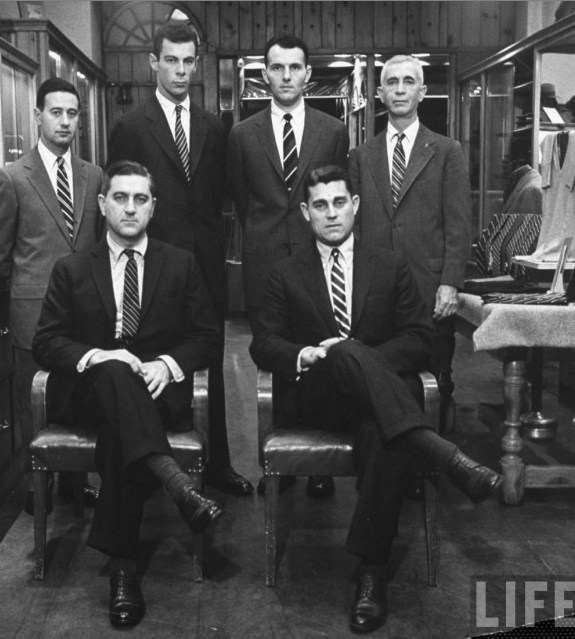

(pictured below: old photos of J. Press)