The best books about men’s style are often social histories, but they’re few and far between. Thomas Girtin’s Nothing but the Best, which documents the tradition of English craftsmanship through the people who actually made such wonderful items, is one of the best books I’ve read on bespoke tailoring and shoemaking. Gilles Lipovtsky’s The Empire of Fashion explores the intersection of our modern obsession with appearance and democratic values. In Ametora, David Marx digs deep into how Japan saved classic American style. And the best works by Bruce Boyer, such as True Style, are about how clothes intertwine with culture.

These books are rare because they take a tremendous amount of work and have a limited audience. But beyond your basic texts on how to combine a shirt and tie, these social histories are so much richer and more interesting than pretty photo books you’ll pick up once and never remember (a genre that makes up most of this field).

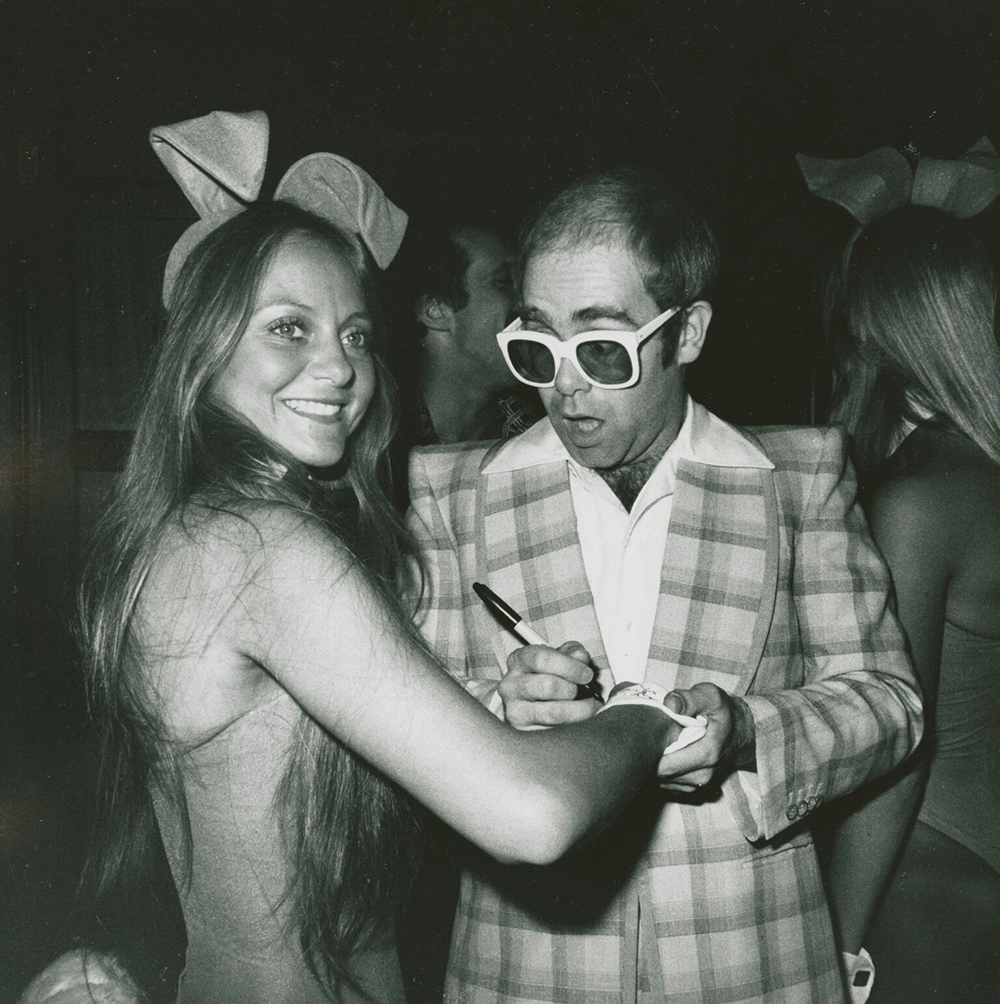

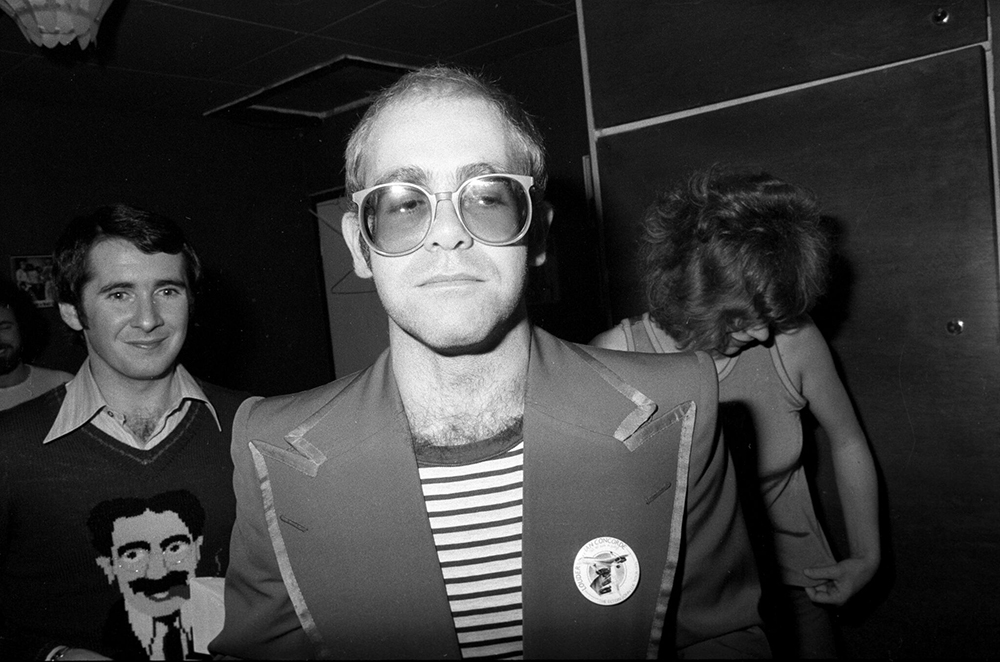

Lance Richardson’s House of Nutter is one of those rare books. It focuses on one of the most unusual tailoring houses in the post-war period, Nutters of Savile Row. If you’re not familiar with the name, you’ve certainly seen their work. Nutters dressed everyone from Elton John to Mick Jagger, Twiggy to Diana Ross. On the album cover of Abbey Road, three of the four Beatles can be seen wearing Nutters bespoke — John Lennon, Ringo Starr, and Paul McCartney. They didn’t coordinate their outfits that day, they just showed up in the clothes they loved most.

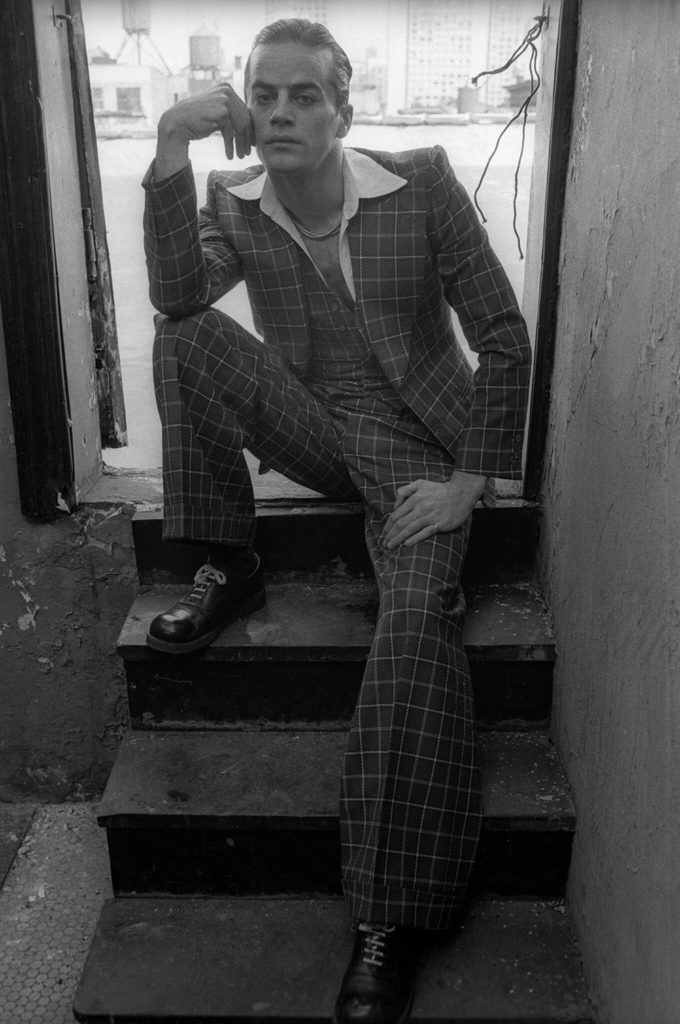

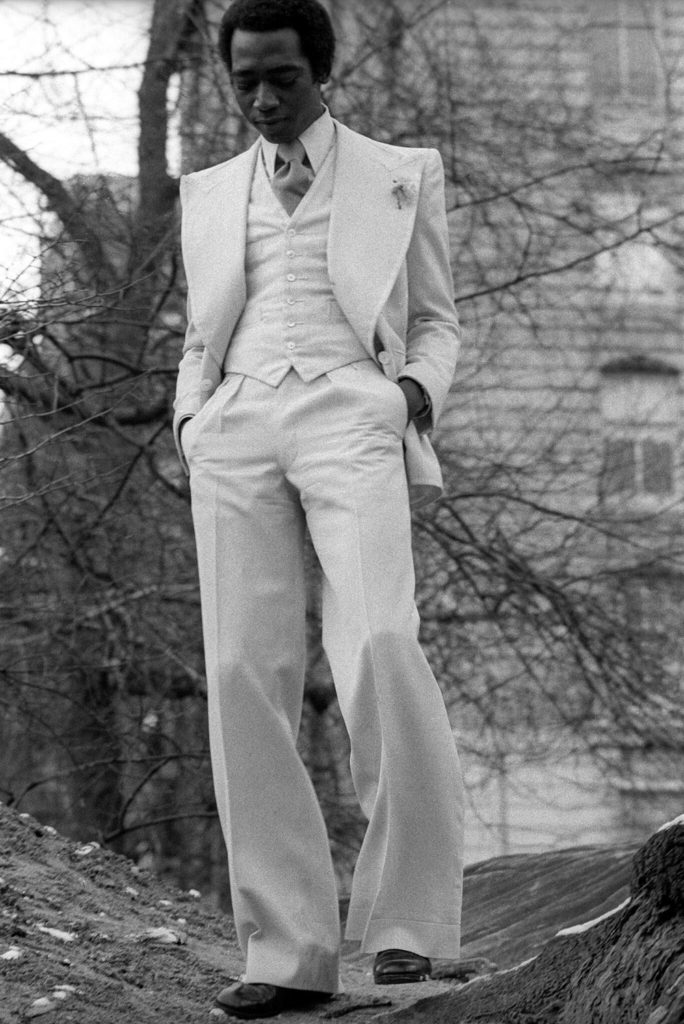

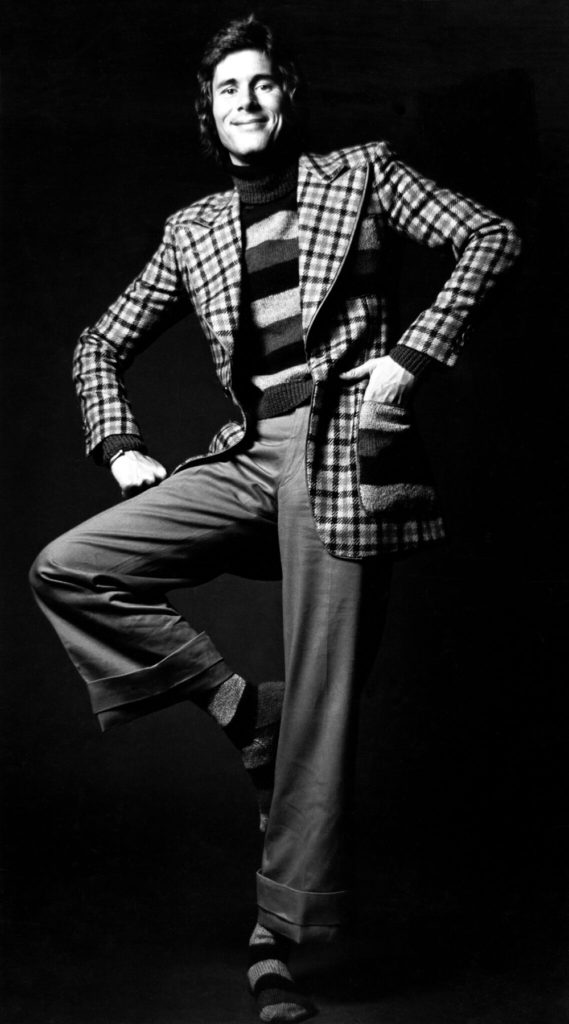

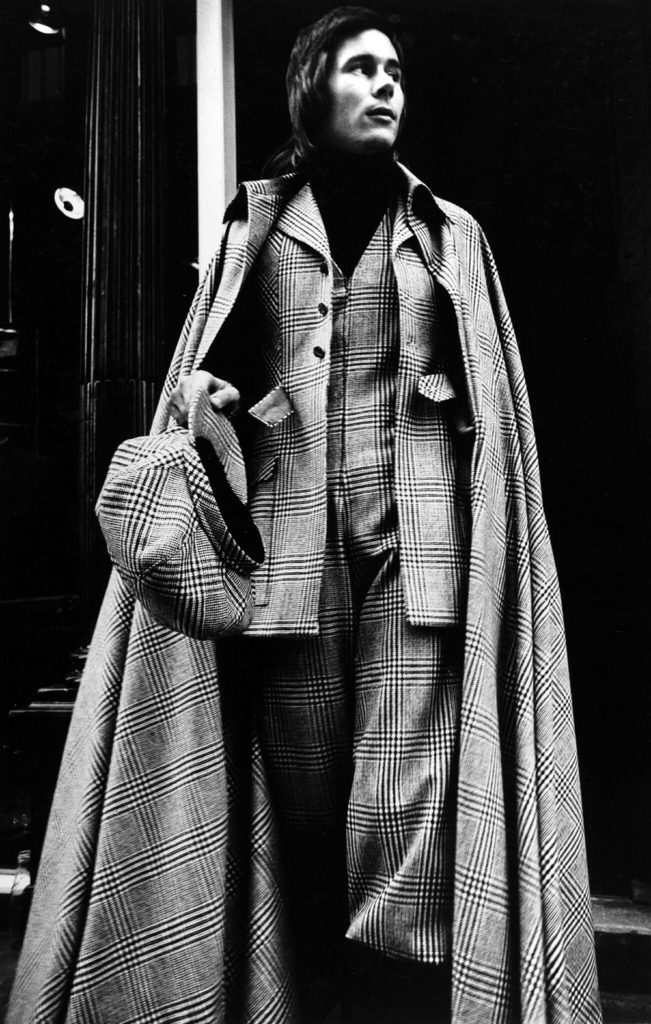

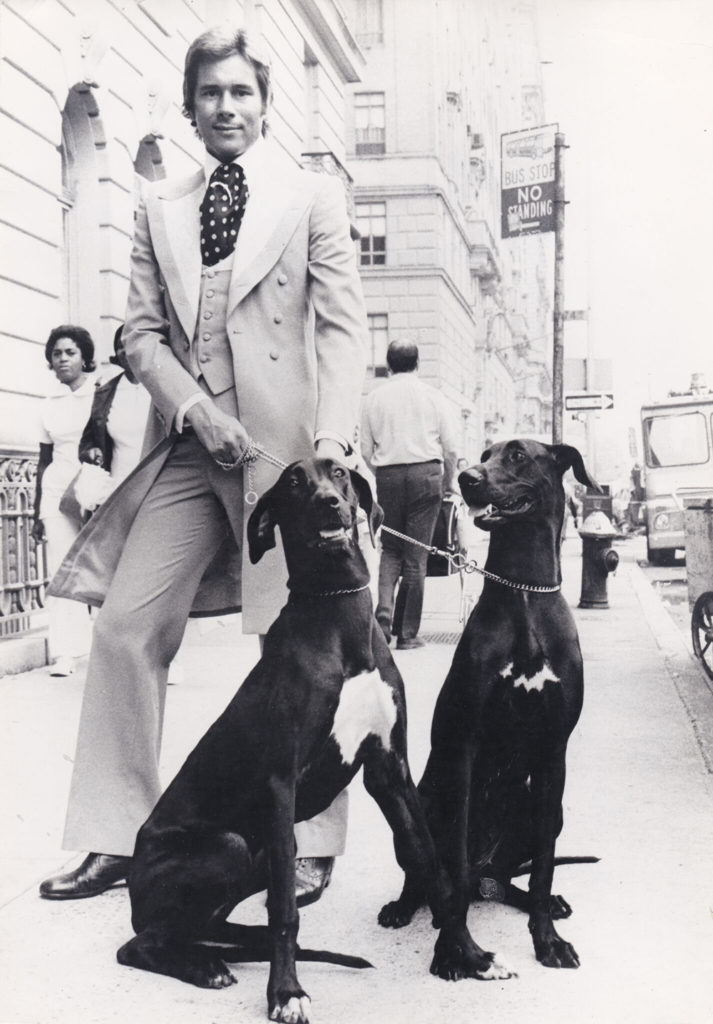

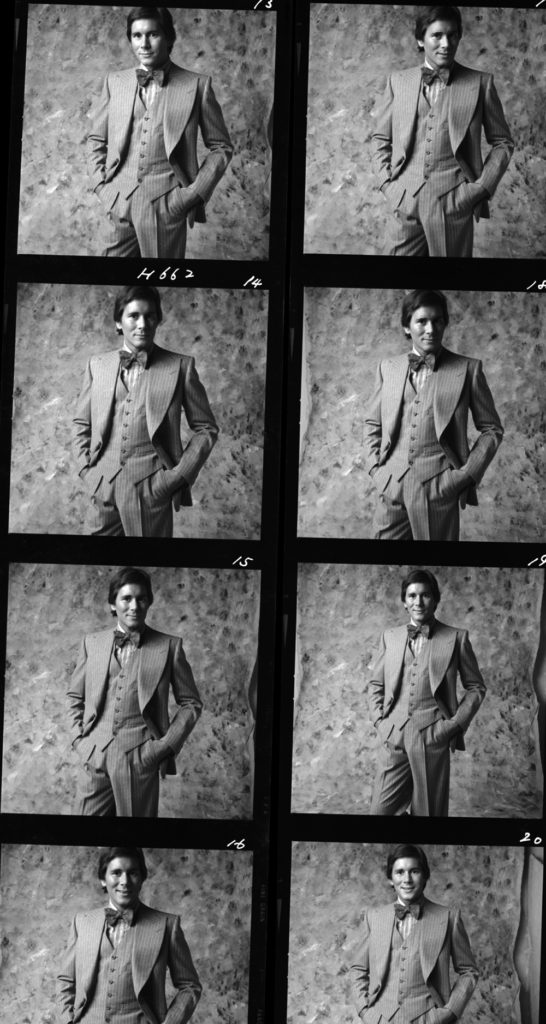

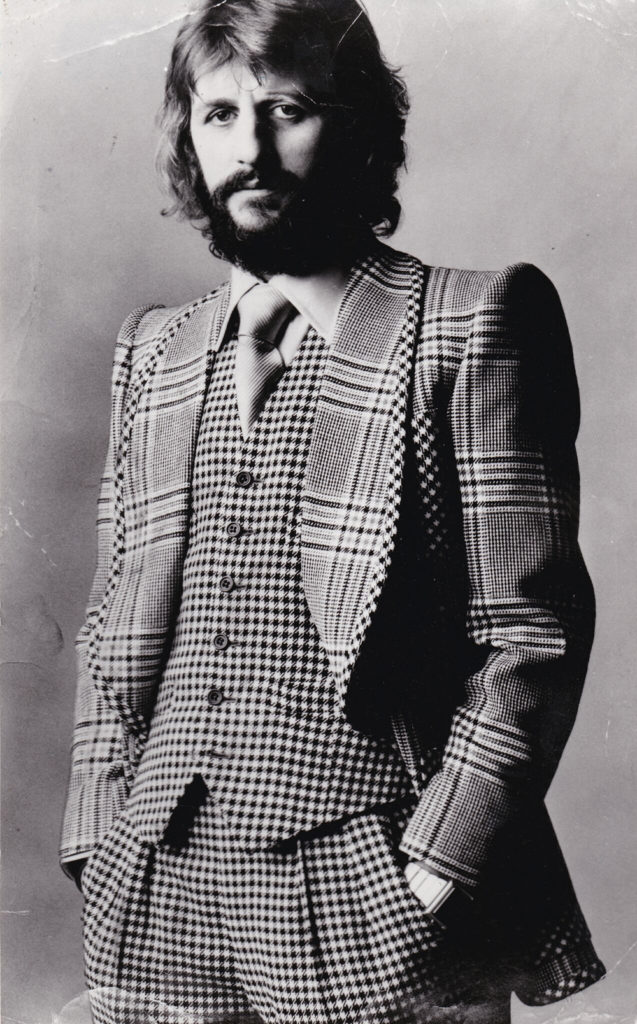

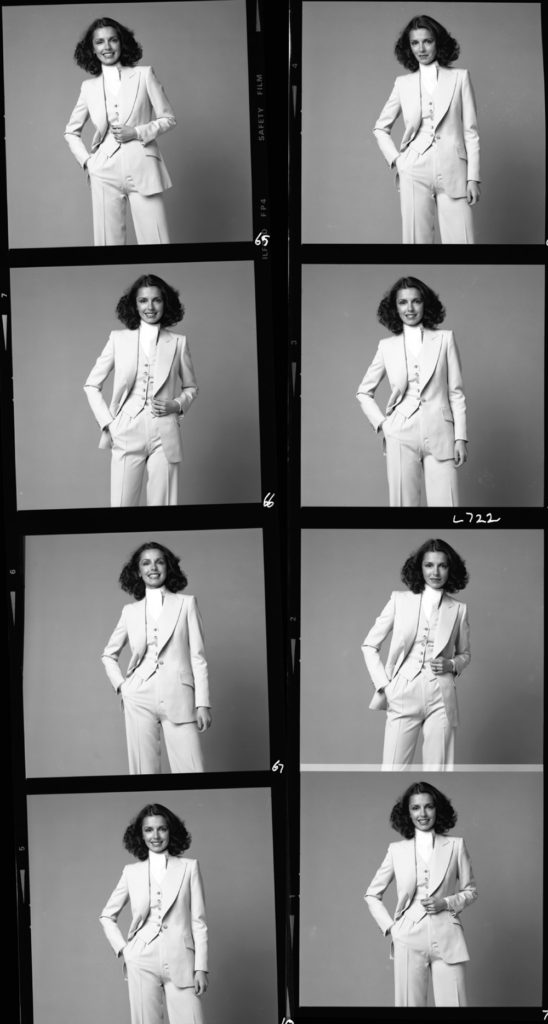

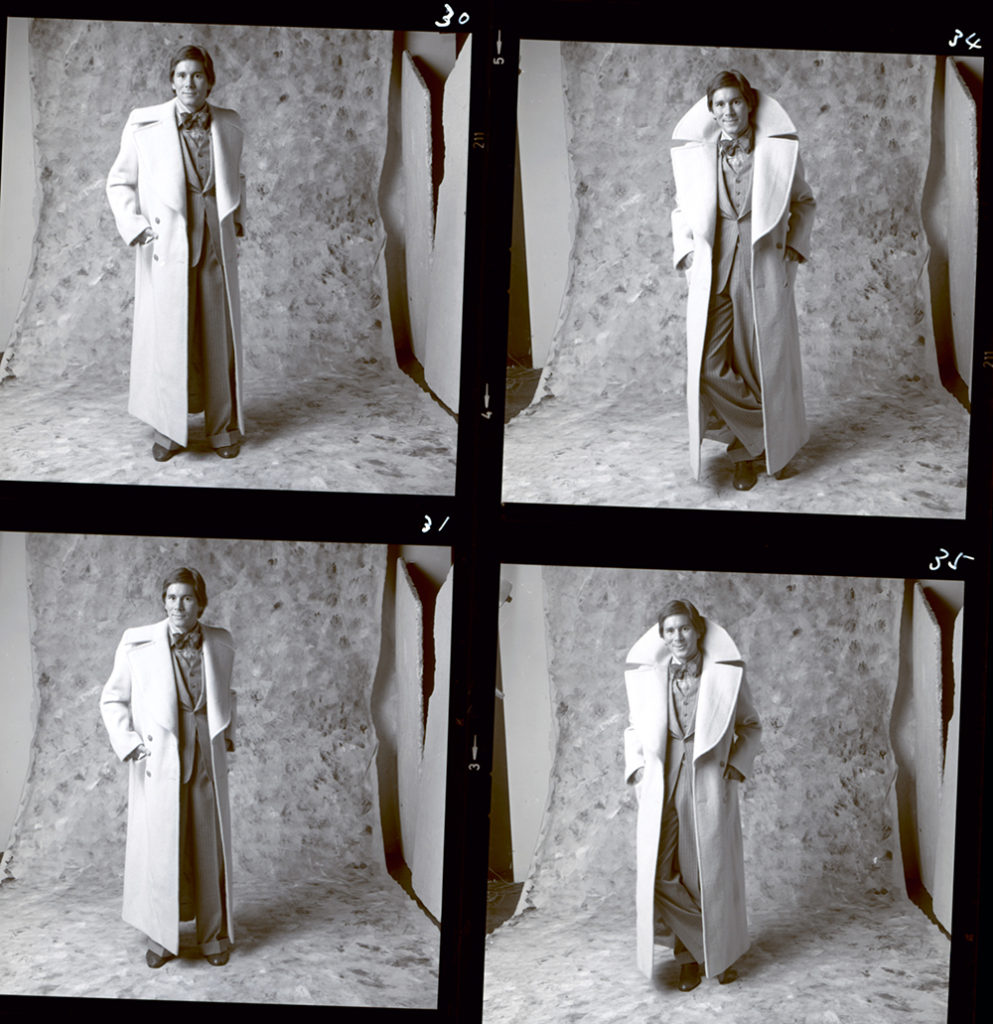

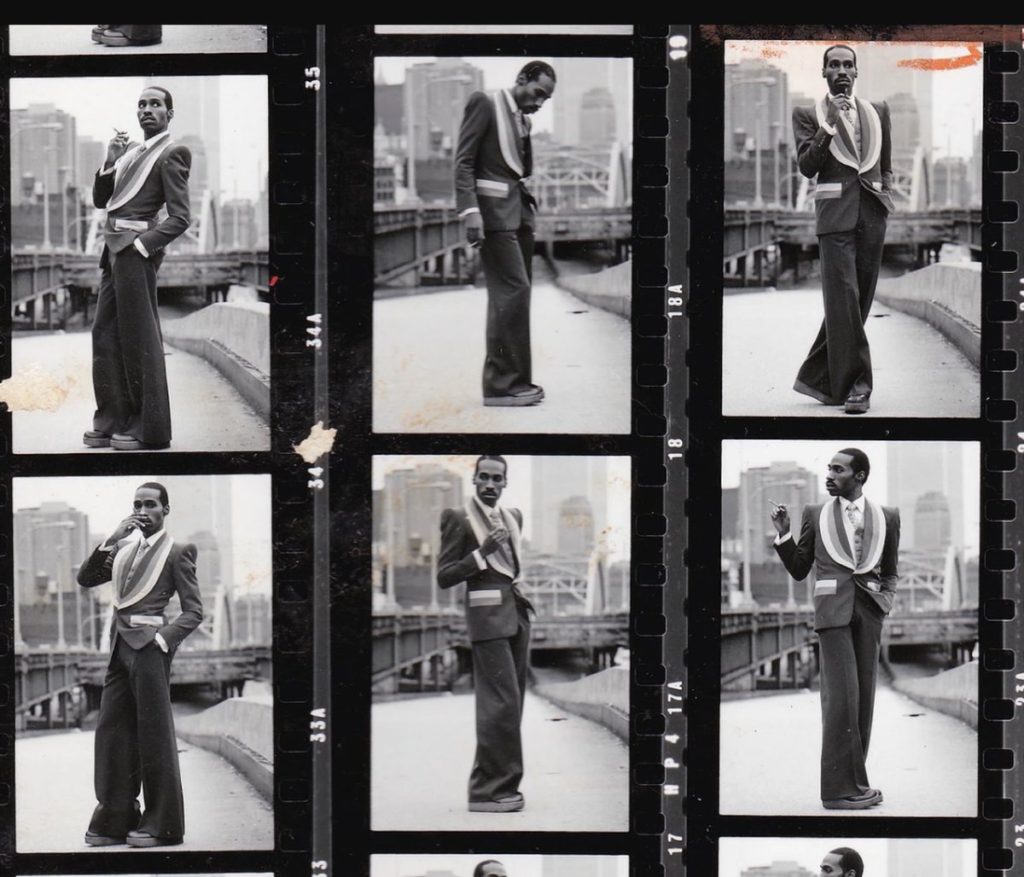

The Nutters look helped to define the uproarious 1970s. It takes a bit of inspiration from traditional English hacking jackets, which were originally built for horse riding. The jackets are long and full-bodied, with square shoulders, nipped waists, and lapels so wide they grazed the wearer’s shoulder joints. Traditional hacking jackets have flared skirts so they can neatly spread out across a saddle. Nutters exaggerated this effect, which gave the wearer an X-shaped silhouette. For those who wanted the full Monty, suits were made from loud plaid fabrics, taped edges, and patch pockets that had been cut on a bias, so they would contrast against the rest of the garment. Punch once described the Nutters look as “an eccentric mix of Lord Emsworth, the Great Gatsby, and Bozo the Clown.” I think of it as wild and chic, even if it’s a bit dated in hindsight.

House of Nutter is a bit about everything. There are some technical details here that will satisfy bespoke tailoring nerds, but it’s wonderfully grounded in a way that’s rare in this genre. Often, talk about bespoke tailoring gets a bit too pompous and pretentious, exaggerating claims about how a custom-made suit will fit perfectly and turn every man into Cary Grant. Richardson captures all of the romance of bespoke tailoring — even getting into nitty gritty details of how a client’s pattern is drafted — without falling for naive illusions. In my interview with him a couple of weeks ago, he told me how he talked to tailors in and around Savile Row, then had the copy proofread and fact-checked by the same tailors to make sure everything is correct.

Then there’s the story of Tommy himself. How he pulled himself out of the working class with little more than the sheer power of his imagination, “so boundless, it seemed, it could overcome all reason and even prove ruinous.” Nutter started off as a salesman at the front of the house at Donaldson, Williamson & Ward, another Savile Row firm. Inspired by the wilder creations by Michael Fish at the time, Nutter saw the possibility of marrying a bolder aesthetic with traditional English craftsmanship. And to realize his creations, he found his cutter in Edward Sexton, who was just daring enough to not brush off his ideas. Sexton was the technical genius behind the Nutters curtain; Tommy himself the visionary and socialite who brought in the celebrity clients.

Much of that socializing happened at gay clubs, Studio 54, and other party venues. Tommy was a gay man who came of age during the oppressive and censorious 1950s, so he met people in underground scenes. As Richardson writes: “Indeed, his life vividly personified forty years of critical gay history. From underground queer clubs of Soho to the unbridled freedom of New York bathhouses to the terrifying nightmare of AIDS – Tommy was there, both witness and participant.”

The book is full of great stories, such as the one of John Lennon and Yoko Ono hanging out in the shop naked when Edward Sexton came into work one day. But there’s also a darker and more depressing side of the story. Tommy Nutter was wildly extravagant and almost drove the firm into bankruptcy. He self-medicated with alcohol, often to the point of blackout, and eventually had a falling out with his cutter, Sexton. In the end, Nutter died of AIDS-related complications. He scaled to a level of success few have seen, but also harbored a dark and tormented personal life that’s all too relatable. One of the remarkable things about the book is how Richardson was able to get people to open up about a very difficult part of their personal histories — Tommy’s brother, David; Edward Sexton; and the many people who worked at the Nutter firm. It gives the book a great sense of depth and intimacy.

Without Nutters of Savile Row, we may have never gotten contemporary designer-tailors such as Richard James and Ozwald Boateng, or the ’70s influenced look of Tom Ford. Richardson’s book captures that wonderful part of history, as well as the cultural forces that gave the clothes meaning. The book is perfectly summed up in the original idea that founded the tailoring house: “the fabric you wore, the way it was cut, the lifestyle you lived — it all went together.”

House of Nutter is available on Amazon and Penguin Books. Richardson also maintains a website, where you can learn more about his other works. He tells us he’s already working on a new book project, although it’s not about fashion.