In menswear, few things are hated as much as synthetics. Every time the topic comes up, someone always says how they’ll happily wear a synthetic, sweat-wicking shirt for workouts, but will shun non-natural fibers in other clothing. They know it’s irrational — synthetic fibers are obviously good for some things — but they just assume man-made fibers are a mark of poor quality.

But what are synthetics and what are they good for? In the world of artificial fibers, different materials are often used for different purposes. In fact, even if you’re a staunch natural-fiber partisan, you definitely have some synthetics in your closet. If not your outerwear (e.g. nylon raincoats, wind resistant shells, and parkas), then at least your underwear. Socks, boxers, and briefs all benefit from having a bit of stretch fiber in order to ensure they retain their shape and stay on your body.

So, here’s a rundown of the five most common synthetic fibers you’ll encounter. We cover the pros and cons of each, and end with a bit of common sense on how to judge quality in clothing.

Rayon

Of all synthetics, rayon should be the least controversial. In fact, some people don’t even consider it a true synthetic because it’s made from plant matter, but it goes through so many chemical processes, it’s often listed as artificial.

If you’re not familiar with the term rayon, you’ve definitely worn it. It’s the umbrella term for cupro, viscose, and modal. You may have also seen it in its trademarked form: Lyocell, Tencel, or, most famously, Bemberg. Those are trade names for different types of rayon, just like Kleenex is a trademarked name for a type of facial tissue.

Rayon is commonly used for linings, including those put into suits, sport coats, and tailored trousers. It’s a smooth, silky material that allows you to slide in and out of your garments easily. And it allows things such as jackets to not catch on your cotton shirts, so that the garment hangs properly. The material is so good that tailors switched out their silk linings for rayon ones generations ago. Silk linings don’t breathe well; they’re relatively delicate and expensive. Rayon, on the other hand, is affordable, doesn’t hold odors easily, and wears cool. This is why you’ll sometimes see it used for pajamas. Rayon has been favored as an alternative to silk for many cases since at least the 1920s.

When You Want Rayon: When you want the smoothness and drape of silk, but also want something that’s affordable, doesn’t hold odors easily, and wears cooler.

When You Don’t Want Rayon: Rayon can be a bit high-maintenance. Like silk, it typically requires hand-washing or dry cleaning. And you generally can’t iron it. On the upside, it sheds wrinkles easily (just hang the garment up overnight or, if you must, steam it).

Polyester

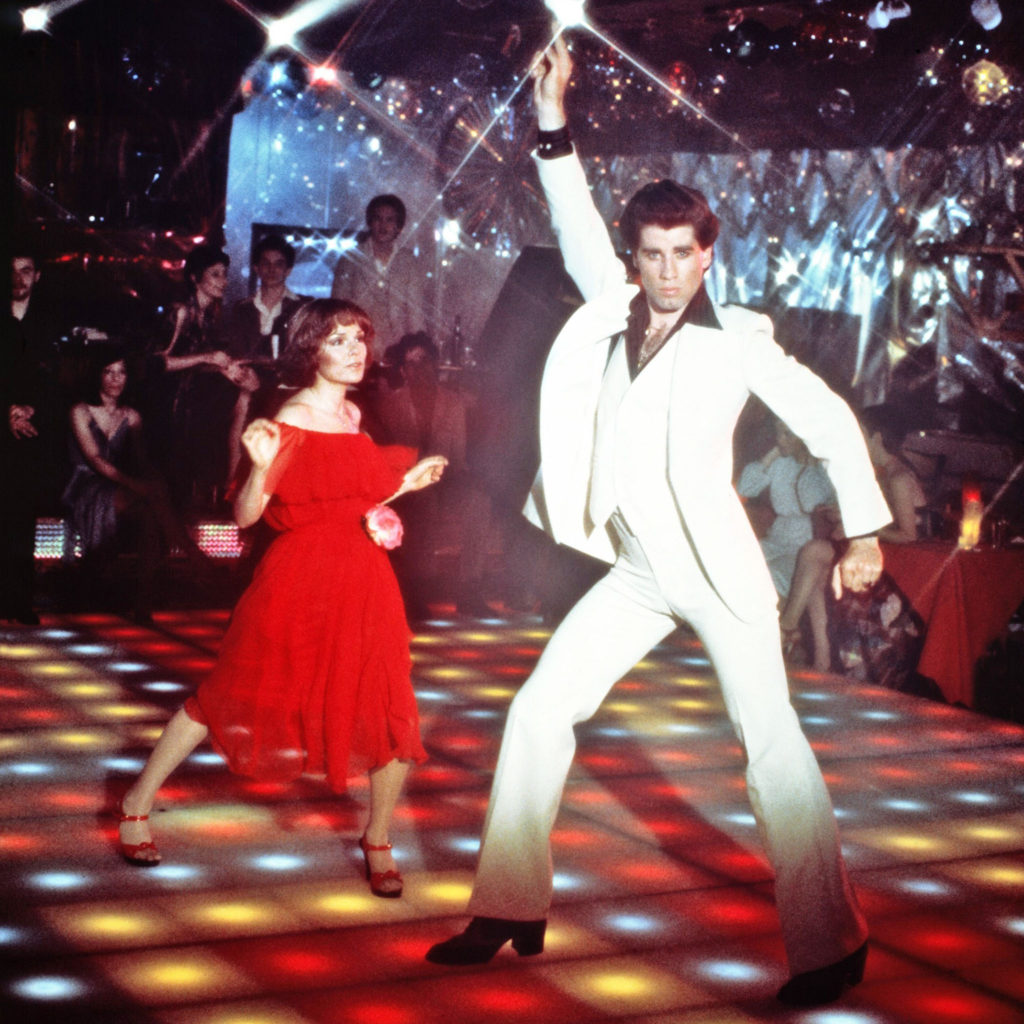

Nothing sounds worse than polyester clothing. Just the mere mention of it brings to mind all those sweaty and uncomfortable polyester suits during the 1970s (the ones in Saturday Night Fever? Yea, those were polyester).

But polyester was not always viewed with such disdain. In the period following WWII, polyester suits were considered techwear, like Nike’s ACG today. This was the era of the wash-and-wear suit, which blended man-made and natural fibers. As the story goes, one summer morning in 1946, while attending a conference in Florida, Joseph Haspel put on his suit and waded out into the Atlantic Ocean, all the way up to his neck. As stunned beachgoers looked on, Haspel returned to shore, went to his hotel room, and hung his suit up to dry. Hours later, he resurfaced as a dinner banquet wearing the same outfit, looking perfectly presentable and convincing attendees that such suits were the wave of the future.

A few years later, Dupont debuted a suit that was made of a fiber they called Dacron (which, for all intents and purposes, is a fancy name for polyester). The suit had been worn for 67 days without a pressing. It had been dunked twice into a swimming pool and then machine washed. And to everyone’s surprise, it was still perfectly wearable. Hart Schaffner & Marx picked up the fiber in 1953 for a new line of Dacron-wool blend suits; Brooks Brothers began using the man-made fiber for shirts, soon following with suits.

All this was made possible because of polyester, which is hydrophobic (which means it repels water). It’s strong and flexible, resists wrinkling, and is machine washable. This is why you’ll often see polyester used for outerwear (Gore-Tex is an evolution of polyester). It’s also sometimes mixed with cotton to produce wrinkle-resistant shirts. And if a spinner is using a weak or fragile fiber, they’ll sometimes mix in a bit of polyester to strengthen a yarn.

At its worst, polyester clothes can look cheap and unnatural. When worn next to the skin, sometimes it’s not very breathable and can feel clammy. But technology has come a long way since polyester was first introduced, and much like fused suits — which are often said to bubble, even if modern ones rarely do — today’s version isn’t always deserving of its bad reputation. Microfibers, for example, are made from polyester and are often used in garments with great success. A lot depends on the specific yarn and how it’s used.

When You Want Polyester: Since the fiber is hydrophobic, it works great for outerwear and gym clothes. It’s water repellant and, depending the weave structure, can also be breathable. Nike’s Dri Fit fabric, for example, is made from a stretchy form of polyester. It keeps your skin dry when you’re working out, so you don’t get that clammy sensation of sweaty cotton sticking to your skin. Fleece outerwear, such as Patagonia’s Retro-X, is also made from polyester.

When You Want to Avoid Polyester: Polyester doesn’t always age that well, and depending on the fabric, it can make a garment look cheap. It’s also subject to static and mildew. Generally speaking, for men’s clothing, you should be fine with polyester if it’s in outerwear or gym clothes. If you see polyester blended with a natural fiber for something else, maybe be a bit more suspicious. It may be that they’re using the material to strength a less-than-great, short staple yarn.

Elastane

The Atlantic has a great article this month by Amanda Mull, which talks about how jean manufacturers have been smuggling spandex into their clothes and marketing them as masculine to gender-sensitive men. “For something as innocuous as slightly less restrictive pants, stretch jeans have caused a lot of hand-wringing among men’s-fashion types over the past couple of years,” she wrote. “Much of it is bound up in what constitutes an appropriate performance of manhood, and whether suffering for fashion, something long considered a feminine burden, is something masculinity requires.” An excerpt:

There are two main ways that clothing companies have chosen to rebrand sitting comfortably as an activity for men. The first is recoding stretch denim as an aid in athletic performance, even though modern fashion jeans aren’t intended to be worn for anything resembling exercise. It’s difficult to parse what kind of rapid motion Banana Republic expects its customers to undertake in Rapid Movement denim, for example, but evoking ideas of athleticism is a common tactic for brands trying to make a case to men for a historically feminine product, according to Ben Barry, the chair of the Ryerson School of Fashion. Invoking athleticism also helps conjure the comfort and ease of athleisure, which is used in other parts of men’s fashion—dress shoes with flexible, cushioned soles, for example—to promise buyers a more casual experience in disguise. […]

The other idea that marketers have invoked to bring men over to the dark side of stretch pants is comfort, which appeals to a slightly less active, slightly less aesthetically concerned conception of modern masculinity. For men who wish they could wear their sweatpants to the office, both traditional brands and upstarts like the Kickstarter darling Alday are here to give them the opportunity. In doing that, they indulge the masculine belief that men should think about how they look as little as possible. There’s clearly a market for such a product: Alday’s Kickstarter sought to raise $15,000, but it ended up with more than $67,000 in support from backers who want to try a denim product that’s knitted like pajamas.

In reality, elastane (the generic name for Lycra or spandex) has been in men’s clothing for years. Without spandex in your socks, they’d bag and fall down. Without it in your boxers or briefs, you wouldn’t be able to keep your underwear up. Elastane is strong, machine washable, wrinkle resistant, and (obviously) very stretchy, with a spring back quality that helps yarns keep their shape. On the other hand, they don’t breathe very well and, eventually, they break down. If you’ve ever heard the “click click click” sound on an old spandex waistband, that’s basically the rubber snapping. And it can’t be repaired.

When You Want Elastane: When you want a bit of stretch to a garment.

When You Want to Avoid Elastane: Elastane is only ever added to a garment when it needs to be stretchy. So the only time you’d want to avoid it is if you dislike stretchy garments.

Acrylic and Nylon

Acrylic is treated as a wool substitute and often used to make wool garments both lighter in weight and cheaper in cost. It performs like animal hair, in many respects. It’s soft, machine-washable, dries quickly, and resists fading. And like wool, it pills with wear (especially the cheap stuff). On the other hand, it doesn’t feel as good as natural animal hair — it often has a dry, artificial hand, and sometimes doesn’t feel as warm. Like polyester, it was first widely used in clothing in the 1950s as part of the wash-and-wear movement, but nowadays you mostly see it in cheaper sweaters.

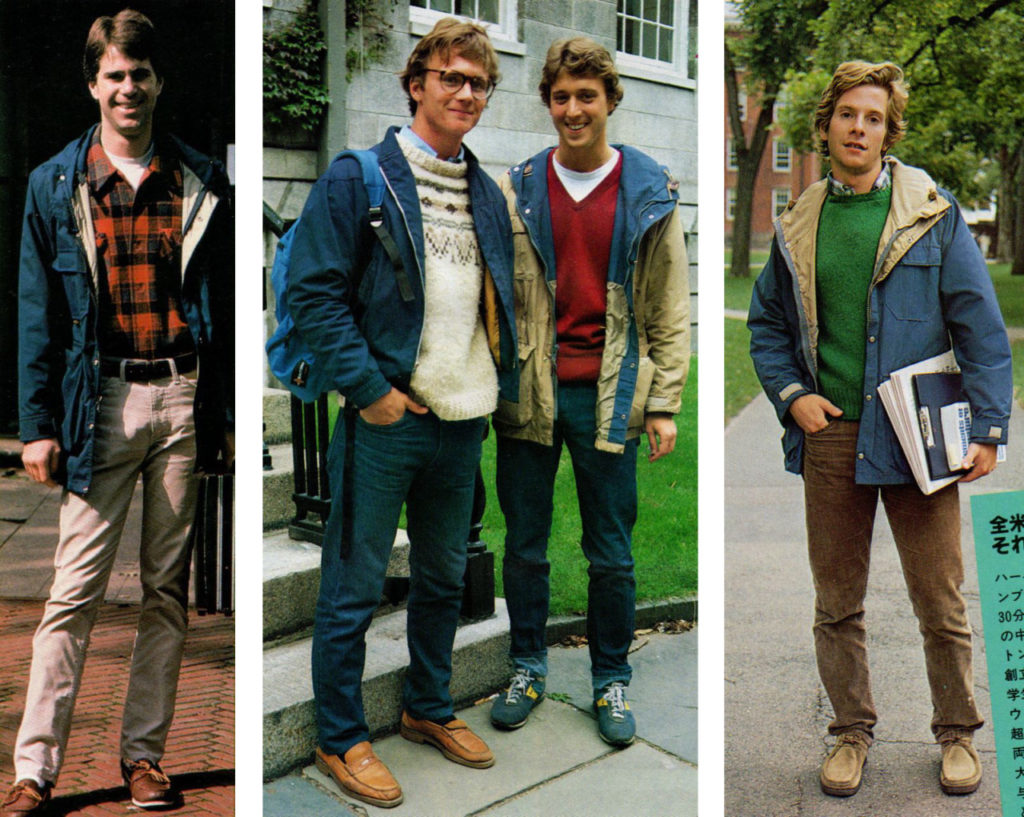

Nylon isn’t at all like acrylic, but it’s similarly straightforward. When it debuted to great fanfare at the World’s Fair in 1938, it was described as being “strong as steel, as fine as a spider’s web.” And it’s that quality that makes it so great. Nylon is a long-chain polyamide that’s naturally flexible only because it’s so micron-thin. When it’s knitted into stockings, it’s stretchy; when it’s woven into fabrics, it’s sturdy and abrasion resistant. You most commonly see it used in outerwear since it has a natural water resistance. Many of LL Bean and Patagonia’s shells, for example, are made from nylon, and Sierra Design’s famous 60/40 mountain parkas are called so because they’re made from a 60/ 40 mix of cotton and nylon. Sometimes you’ll also see nylon added to a yarn in order to give it strength or texture.

When You Want Acrylic and Nylon: An acrylic-blend sweater can be good if you want something that’s a bit lighter in weight and more affordable. Pure acrylic sweaters can also be good substitutes for animal-hair knitwear if you’re vegan. Nylon, on the other hand, is typically favored for its water resistance, abrasion resistance, and strength. You’ll often see it used in socks to make a thin wool yarn stronger, or in outerwear for its weather resistant properties.

When You Want to Avoid Acrylic and Nylon: Sometimes these fibers are blended with wool or cotton in order to give the resulting yarn a more unique texture, but more often than not, they’re used to cut cost. Since nylon isn’t breathable, this can dramatically cut down on the garment’s comfort (unless you’re wearing a pure nylon shell, in which case you kind of know what you’re getting into).

At the End of the Day, Use Common Sense

A few years ago, I interviewed Jeffery Diduch, the Vice President of Technical Design and Quality for Hickey Freeman, one of the largest suit manufacturers in North America. Jeffery has a ton of experience in factory production and is a no-nonsense kind of guy (his blog, Tutto Fatto a Mano, is a must read if you’re interested in the technical aspects of tailoring). He put the issue succinctly.

For Jeffery, making clothes is a lot like making food. If you’re running a restaurant, you can hire the best chefs and buy the most expensive ingredients. But if you want to sell your dish, you may need to think about what needs to be sacrificed in order to meet a certain price point. Perhaps you hire skilled, but less renowned chefs. Maybe you use slightly lower-grade olive oil, but decide the truffle oil must be kept if the dish is to have its signature flavor. This is very much like what designers do. There are hundreds of steps that go into making a garment, and each designer has to decide which steps are most important to him or her. These calls are going to be very subjective.

Synthetics have their advantages and disadvantages. Since they’re man-made, companies have greater control over how the yarn is produced, which can result in some superior performance or texture. This can mean giving a garment some real added benefits, such as stretchability or waterproofing. At the same time, sometimes these fibers are added to cut cost — maybe in ways you don’t prefer. Some synthetics are less breathable, have poor absorbency, and are bad choices in warm climates since they trap heat and sweat against your skin.

At the end of the day, the best marker for quality isn’t the garment’s fiber composition tag, but rather the brand’s name. Let the brand’s reputation and your previous experiences with the company be your guide. A bit of acrylic might be added to an Engineered Garments sweater in order to create a more interesting yarn. Nylon and spandex are also needed in dress socks, even ones that are top-of-class. But that $20 pure acrylic sweater from ASOS? You already know.

There may be one reason to avoid synthetics where you can: man-made fibers are washing into our oceans along with our laundry water, where they’re consumed by fish and then ending up in our food chain. Since artificial fibers take forever to decompose, our marine life at this point is literally drowning in plastic. When I talked to some environmental experts about this, however, they noted that purely natural garments can have their own environmental impacts as well. The real solution may not be to avoid synthetics, but to limit your consumption. Buy fewer clothes and wash only when necessary.